Spirits, ghosts, deities and monsters

With a population of around ten thousand, the indigenous Paiwan people of Taiwan forms the island’s third-largest Formosan ethnic group. Traditional Paiwan territory span both sides of the southern portion of Taiwan’s central mountain range. Their homeland stretches from the highlands around Damumu Mountain southward to the plains of the Hengchun peninsula, at the very southern end of the island, as well as the southeastern hills and coastal plains of Taiwan. The loose Paiwan confederacies are composed of two main groups, which are, in turn, made up of numerous smaller, highly diverse autonomous units. Individual Paiwan bands and villages are traditionally presided over by local aristocracies that oversee each unit’s political, military and religious affairs. The Paiwan is a proud and powerful indigenous community in southern Taiwan. Their distinct culture and customs are reflected in their traditional art, which often features sacred serpent motifs (especially of the Hundred-Pacer) inspired by their native mythology. [Taiwan]

Eight Categories of Taiwanese Folklore

What is Folklore?

Folklore—the traditional customs, beliefs, stories and sayings of a community, passed down through generations largely by word of mouth. Folklore is concerned with the shared memories and heritage of everyone within a community and every community has its unique set of “people’s customs.” These are stories from Taiwan’s indigenous Austronesian—also called Formosan—communities. They represent the mind-bogglingly diverse cultures and languages of Taiwan’s “First Nations” who have called the island home for tens of thousands of years.

These are stories from Taiwan’s indigenous Austronesian—also called Formosan—communities. They represent the mind-bogglingly diverse cultures and languages of Taiwan’s “First Nations” who have called the island home for tens of thousands of years.

In the woods, amidst dead and dying brethren, the old chieftain—Mona, son of Rudao—reflected.Japan’s empire reached Taiwanese shores when Mona Rudao was a youth of 15. As the eldest sonof the chief of the Seediq people, Mona was invited by Taiwan’s Japanese governor to visit the empire’s home islands. Young Mona travelled to Japan and saw the splendid palaces of Kyoto, the factories of Tokyo and the military academies of Nagoya. The young Seediq was deeply awed by Japanese imperial power. When he returned to Taiwan, Mona Rudao, who succeeded his father as the new Seediq chieftain, knew he could not fight the Japanese. No, he chose to work with those who called themselves his colonial masters. He knew better than to draw the ire of the Japanese upon his people. In 1920, the empire sought to subdue the fierce Atayal bands of central Taiwan. Tapping into existing Taiwanese rivalries, the Japanese sought indigenous help. Eager to gain favour, Mona Rudao and his people answered the call. Under the Rising Sun Flag, a coalition of Seediq warriors and Imperial soldiers raided Atayal settlements. The Seediq and the Japanese, out of necessity and out of prudence, were to be friends. As the Japanese said, these savages had been “tamed.” But the Japanese grew arrogant in their rule of Taiwan, and that fragile friendship was to be tested.

Between 1895 and 1945, Taiwan was a key colonial possession of the Japanese empire. Decades of Japanization policy greatly shaped Taiwanese life in this period. Japan’s influence, though largely overshadowed by the impact of Sinitic and Formosan cultures since WWII, continues to be an integral part of understanding the Taiwanese experience and Taiwan’s folk heritage.

Taiwan’s Big-Cat Folklore and History

In 1895, a certain Sino-Japanese treaty stipulated that Taiwan would henceforth become Japan’s first major overseas colony. This was, of course, much to the surprise of the Taiwanese people who, naturally, didn’t have a say in the matter. It’s not as if they lived there or anything…. Anyway, the people of Taiwan took matters into their own hands and proclaimed the independent Republic of Formosa. Remarkably, as far as this article is concerned, the adorable flag design they adopted featured an incredibly loveable Formosan Tiger as the republic’s symbol. The people of Taiwan now had a banner to rally under in their resistance against Japanese rule. The disparate Han and Formosan ethnic groups of the island—the Hoklo, Hakka, Saisiyat, Seediq and others—came together in numerous uprisings against colonialism. Alas, Japan’s Imperial Army was formidable, indeed, and Taiwan’s Republic of Formosa was crushed the same year it was founded. After several more large-scale revolts, Taiwan was gradually Japanized and became what Japan called its “model colony.” The Formosan Tiger was tamed—for now.

These are stories passed down in the many distinct Sinitic, Han or Chinese languages and dialects spoken throughout Taiwan—Taiwanese, Hakka and Mandarin. They include stories born on the island from the experiences of Han settlers since the 17th century as well as tales that were brought to the island directly from the continent.

Taiwanese Bigfoot: The Tale of a Giant

There are actually a number of Taiwanese legends and folktales featuring individuals and creatures similar to the notorious Bigfoot. Known in Taiwanese as tōa-kha-sian (dàjiǎo xiān in Mandarin), these “Bigfoot” characters are found in stories that have unexpected origins in Taiwan’s 17th-century Dutch colonial period. The following is a folktale from Pingtung. It is set sometime after the Dutch period—likely during Taiwan’s era under Qing rule (1683–1895)—and is about a giant by the name of Xǔ Dàpào.

Bigfoot the Hero

One day, Xǔ Dàpào was napping at the foot of a tree in the mountains near his village. He had been chopping trees and gathering firewood, which was hard work even for a giant like him. So he decided to take a break. But then, while Xǔ Dàpào napped, a band of Taiwan’s indigenous Austronesian headhunters from the highlands appeared. This group of warriors was on a raiding mission to Xǔ Dàpào village. The slumbering giant got up and began to battle the indigenous fighters. He was successful and was able to fend off the raiding band—successfully protecting his village.

Folktales are stories passed down through generations, usually through word of mouth, within a community or culture. Most of these stories originate in popular culture and contain the cultural memories, ideals and philosophies of their communities.

In the Beginning

In the beginning, the unimaginable vastness of the universe was contained within a single egg. Inside the egg, a giant named Pángǔ slowly developed over tens of thousands of years.One day, there was a rumble from within the egg. A crack stretched across the surface of its shell and soon, the egg burst open. The Big Bang. From within the egg’s initial singularity, the giant, along with the rest of the nascent world, emerged.

Pángǔ awoke from his slumber to darkness and a tangled mess of mass and elements. The startled giant grabbed an axe and gave a powerful slash. The elements became separated. The lighter elements floated upwards and became the sky, while the heavier elements sank down and became the earth. Pángǔ tried to stretch his stiff limbs. But, “oops,” he said as the back of his head bumped against the sky. In this newly formed world, the sky was quite low and close to the earth. “This will not do,” reflected the gentle giant and, like the Greek god Atlas who shouldered the weight of the world on his back, Pángǔ raised his arms towards the sky and began to push. Each day, Pángǔ grew a meter, and each day the sky became further separated from the earth. This tiring labour continued for many tens of thousands of years until, finally, the sky was high and far from the earth. Then, the spent giant Pángǔ, finally able to stretch out his arms and legs, collapsed from exhaustion.

Folklore is an important component of a people’s history—both resulting from and creating it. Island Folklore documents not just the traditions and narratives of Taiwan’s folk culture, but also the unique history of the island’s diverse peoples.

How It All “Bi Gan”: A Surname Origin Story

Family names are an interesting topic. Often, they tell stories. The Scottish clan MacDonald, for example, are literally the “sons of Dhomhnuill“—or Donald. Also consider the Rothschild family, of banking-conspiracy-theory fame. They once lived in a Frankfurt house decorated with a red shield, which in German is called a rothen Schild. Surnames may also describe occupations or places of origin. Smiths were metalworkers while Mercers were merchants. François Hollande, the former French president, is a descendant of 16th-century immigrants from the Low Countries, the most famous region of which is Holland. Most Taiwanese surnames today, whether for indigenous individuals or those with continental ancestry, are Chinese in origin. Some of the most common are Chen, Huang, Chang and Lee. Two other extremely common Taiwanese family names—Lin (meaning “forest”) and Wang (meaning “king”)—actually share an origin story that dates back over 3,000 years to a sage named Bi Gan. Yes, if you’ll excuse the pun, this is indeed the story of how it all Bi Gan for the Lin and Wang families of Taiwan.

Legends are a community’s traditional stories that are popularly regarded as history or are based on historical events. These tales often elaborate on the lives of famous or influential figures in the past.

Chop-Chop: The Folklore of Chopsticks

Chopsticks are ubiquitous on the dining tables of East Asia. In Mandarin, they are called kuàizi (筷子) and, in Taiwanese, they are known as tī (箸). These utensils aren’t just essential to Taiwanese dining, they are steeped in stories and traditions! Below is a quick rundown of Taiwanese chopstick folklore!

The primary function of mythology is to provide explanations for certain natural or social events. These traditional stories typically feature supernatural beings or occurrences and often concern the early history or origin of a people.

Fire and Water

This story follows the events of The Mother Goddess.It involves a catastrophic hole that opened up in the sky, one that the mother goddess Nǚwā had to patch up with urgency in order to preserve her mortal children. That hole was the result of a violent battle between two gods: the god of water, Gònggōng, and the god of fire, Zhùróng.

According to this myth, up in heaven, in the abode of the gods, dwelled the prideful and vicious god of water, Gònggōng. The water god had the face of a man and the body of a serpent. Red hair grew from his head, which was filled with violent thoughts. This god, however, was not very clever and is easily provoked, something his sycophantic attendant, the devious spirit, Xiāngliǔ, took full advantage of. The spirit Xiāngliǔ, like his master the water god, was also a human-headed serpent. He was green from head to tail and possessed nine brains, all of which contrived a constant stream of terrible and malicious ideas

Traditions are beliefs, ideas, customs and practices passed down from generation to generation within a community. These include religious or ritualistic practices and often trace their origin to certain folktales, legends or myths.

Story of Yuma

尤瑪傳奇

尤瑪·達陸是台灣原住民泰雅族的傳奇人物。

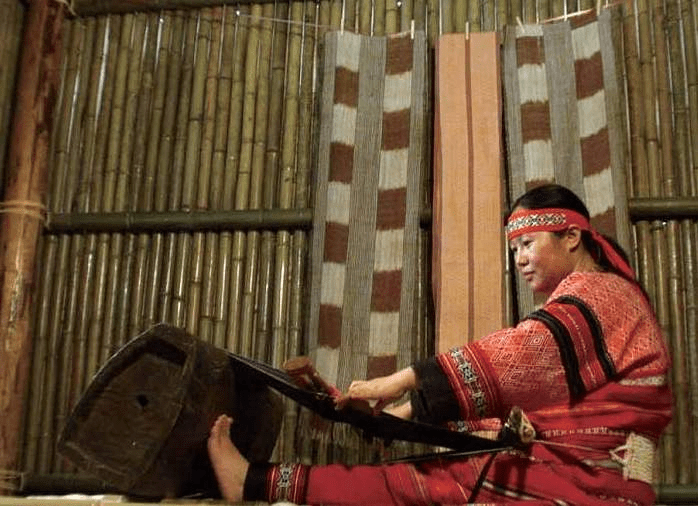

Yuma Taru is a legendary figure among the indigenous Atayal people of Taiwan.

泰雅族是台灣十六個原住民中,分布最廣的一族,其分布區域橫跨宜蘭縣、新北市、桃園市、新竹縣、苗栗縣、臺中市與南投縣,佔臺灣中北部三分之一的山區。

The Atayal people are one of 16 officially recognized indigenous tribes of Taiwan. Among indigenous tribes, they control the largest territory. The Atayal homeland is in the northern one-third of Taiwan’s mountainous regions, including parts of Yilan, Taipei, Taoyuan, Hsinchu, Miaoli, Taichung and Nantou.

2016年,52歲的尤瑪獲得政府頒發 「重要傳統藝術保存者」的榮譽,表彰她二十多年來致力於保存、重製、發揚泰雅族傳統織物的貢獻與成就。

In 2016, the 52-year-old Yuma was designated an important conserver of traditional art by the Taiwanese Ministry of Culture. The honour highlights the over two decades she dedicated to preserving, recreating and promoting traditional Atayal textile and fabric arts.

流淚播種

尤瑪出生於1963年苗栗縣的泰安鄉,父親是原籍湖南的軍人,在1949年隨著蔣介石政權從中國撤退到台灣來。後來,娶了一位泰雅族的姑娘—尤瑪的母親。

Sowing the Seeds

Yuma was born in 1963 in Tai’an Township, Miaoli County, Taiwan. Her father was a soldier, originally from China’s Hunan Province, who escaped in 1949 to Taiwan with Chiang Kai-shek’s regime when communism took hold in China. He would go on to marry an indigenous Atayal woman—Yuma’s mother.

1980至1990年代是台灣反抗獨裁政權、要求民主,提倡多元文化及本土化運動風起雲湧的時代。當時原住民自覺和爭取自身權益的聲音也沒有缺席。尤瑪也參與了原住民的復興運動。1997年她與一群泰雅族知識青年組成苗栗縣泰雅北勢群文化協進會,從事部落兒童、婦女、青少年的民族教育工作及傳統祭典的推展,而尤瑪負責研究已經凋落的泰雅族織布文化。

The period from 1980 to 1990 in Taiwan was marked by movements against authoritarianism, toward democratization and the promotion of Taiwan’s native, multicultural heritage. It was a time of increasing self-consciousness for Taiwan’s indigenous peoples and demands for more representation. Yuma was active in the indigenous revival movement. In 1997, she formed a cultural association for the Beishi Atayal sub-group in Miaoli with a group of Atayal colleagues. They provided cultural education to Atayal children and women—passing on invaluable cultural inheritances to a new generation of the Atayal people. Yuma was put in charge of researching the critically endangered Atayal tradition of weaving.

http://www.indigenouspeople.net/Taiwan/

http://www.indigenouspeople.net/taiwan.htm

Indigenous Peoples of Taiwan

by: Rebecca C. Fan

Out of Taiwan’s total populations of 21.3 millions, there are more than three hundred and fifty thousand who are indigenous tribal peoples. Distinguished from the majority Han Taiwanese, indigenous tribal groups are part of the so-called Malayo-Polynesians.

Linguistically, they are recognized as sub-groups of the Austronesian-speaking family. Therefore they are also called the Austronesians. Despite the fact that their languages are derived from the same root, the languages they currently speak are not mutually comprehensible between groups. All indigenous tribal groups are generally known and officially recognized as the Indigenous Peoples of Taiwan.

Some Taiwanese anthropologists refer to them as the earliest inhabitants of Taiwan. They themselves prefer to be addressed by their tribal names.

They are the:

Ami, Atayal, Paiwan, Bunun, Rukai, Puyuma, Tsou, Saisia, Yami (Da-Wu) and Pinpu.

According to anthropometric measurements and genetic studies conducted by the Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan, the results indicate substantial differences among them. Based on social-cultural comparisons, the differences are even more interesting. In terms of family structure and kinship, there are three groups characterized by stem family structure with an equal status for both patri and matrilateral kin (such as the Paiwan, Rukai, and Puyuma). There are three patrilineal societies with patrilocal residence (such as the Bunun, Tsao, and Saisai), one matrilineal society with matrilocal residence (the example is the Ami), still two others are characterized by nuclear family units, patrilocal residence and parallel status for both bilateral kin.

Contemporary Song Lyrics

composed by

Indigenous Peoples of Taiwan

Forever will be Indigenous Peoples

by DagaNow (Paiwan/Rukai)

Mountain will always be mountain

Indigenous Poeple will always be Indigenous People

Wherever you go, wherever you end up

Indigenous People will always be Indigenous People

by Chanien (Puyuma)

Isn’t it true that only when one departs, does one feel homesick?

Although I am still standing on this land I called home,

no pre-warning,

I become emotionally furious and have no peace.

Because my father had once said to me:

“This land used to be our land……..”

Really Want To Go Home

by DagaNow (Paiwan/Rukai)

Indigenous Peoples straying in the city

Do not have much luxury to dream

Blood with special mark flowing in the body

Do not know if tomorrow will still be the same

Indigenous Peoples living under uncertainty

Wounded souls want to go back to their homeland

Have been reluctantly in disguise for so long

Do not know if tomorrow will still be the same

Really want to go home

Really want to go home

At the end, Indigenous Peoples are all the same

Young men earn their livings in city factories

Young girls are forced into prostitution

Realized that life is no easy task

Do not know if tomorrow will still be the same

What will be the future for Indigenous Peoples

To speak of it made my heart feel sore

Ask for the answer made my heart go panic

Do not know if tomorrow will still be the same

Really want to go home

Really want to go home

At the end, Indigenous Peoples are all the same.

Other Sites:

Taiwanese indigenous peoples

Taiwanese indigenous peoples (formerly Taiwanese aborigines), Formosan people, Austronesian Taiwanese, Yuanzhumin or Gaoshan people, are the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, who number about 569,000 or 2.38% of the island‘s population. This total is increased to more than 800,000 people if the indigenous peoples of the plains in Taiwan are included, pending future official recognition. Recent research suggests their ancestors may have been living on Taiwan for approximately 6,500 years. A wide body of evidence suggests Taiwan’s indigenous people maintained regular trade networks with regional cultures before major Han (Chinese) immigration from continental Asia began in the 17th century.

Taiwanese indigenous peoples are Austronesian peoples, with linguistic and cultural ties, as well as some genetic drift to other Austronesian peoples. Taiwan is the origin of the oceanic Austronesian expansion whose descendant groups today include the majority of the ethnic groups of the Philippines, Micronesia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, East Timor, Madagascar, and Polynesia.

For centuries, Taiwan’s indigenous inhabitants experienced economic competition and military conflict with a series of colonizing newcomers. Centralized government policies designed to foster language shift and cultural assimilation, as well as continued contact with the colonizers through trade, inter-marriage and other intercultural processes, have resulted in varying degrees of language death and loss of original cultural identity. For example, of the approximately 26 known languages of the Taiwanese indigenous peoples (collectively referred to as the Formosan languages), at least ten are now extinct, five are moribund and several are to some degree endangered. These languages are of unique historical significance since most historical linguists consider Taiwan to be the original homeland of the Austronesian language family.

ATAYAL

Village In The Clouds

Yami Legend of the Founding of Hungtou Village Story

Legend of Tribal Origins Story

Puyuma Legend of Tribal Origins Story

Tsou Legend of the Origin of Headhunting Story

Bunun Legend of the Flood Story

Atayal Legend of Shooting the Sun Story

Saisiat Legend of the Origin of the Dwarf Spirit Ceremony Story

Rukai Legend of the Founding of Villages Story

Paiwan Legend of the Flood

How the Taiwanese Aborigines Shaped Modern Asia

Preserving tribal history in Taiwan

Taiwan’s indigenous fighting for their land

A full-time aboriginal radio station, “Ho-hi-yan”, was launched in 2005 with the help of the Executive Yuan, to focus on issues of interest to the indigenous community. This came on the heels of a “New wave of Indigenous Pop”, as aboriginal artists, such as A-mei, Pur-dur and Samingad (Puyuma), Difang, A-Lin (Ami), Princess Ai 戴愛玲 (Paiwan), and Landy Wen (Atayal) became international pop-stars. The rock musician Chang Chen-yue is a member of the Ami. Music has given aborigines both a sense of pride and a sense of cultural ownership. The issue of ownership was exemplified when the musical project Enigma used an Ami chant in their song “Return to Innocence“, which was selected as the official theme of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. The main chorus was sung by Difang and his wife, Igay. The Amis couple successfully sued Enigma’s record label, which then paid royalties to the French museum that held the master recordings of the traditional songs, but the original artists, who had been unaware of the Enigma project, remained uncompensated.