http://www.indigenouspeople.net/chumash.htm

Chumash Literature

“There is no ‘better’ or ‘worse,’ only different. That difference has to be respected whether it’s skin color, way of life, or ideas. The Chumash have a story about this. It begins with a worm who is eaten by a bird. The bird is eaten by a cat whose self-satisfaction is disrupted by a mean-looking dog. After devouring the cat, the dog is killed by a grizzly bear who congratulates himself for being the strongest of all. About that time comes a man who kills the bear and climbs a mountain to proclaim his ultimate superiorty. He ran so hard up the mountain that he died at the top. Before long the worm crawled out of his body.”

Kote Kotah

Chumash Cosmology

The Chumash (California) referred to meteors as Alakiwohoch, which simply meant “shooting star.” They believed a meteor was a person’s soul on its way to the afterlife.

Another form of record keeping were rock petroglyphs, or pictures carved into rock. The western United States abounds with these pictures, but any dating is virtually impossible. Once again it is frequently difficult to determine whether the object carefully carved into rock is a meteor or a comet.

One rock drawing frequently debated as to its exact depiction was produced by the Ventureo tribelet of the Chumash at Burro Flats. A pair of disks with long tails are located on the wall of a cave and have been interpreted by Travis Hudson and Ernest Underhay (1978) as portraits of a comet “seen over an interval of a few days or weeks.” On the other hand, E. C. Krupp (1983) has pointed out that “the images have a dynamic appearance that suggests rapid movement and change. If they are celestial at all, I would associate them with meteors, and, in particular, with the especially bright and dramatic type known as fireballs.”

Stories

California’s first oceanographers: The Chumash Indians

Chumash Indian Life/The Santa Barbara Museum

Chumash Myths and Stories

Chumash, the “First People”

History of the Chumash Indian People

Making of Man

Sky People and the game of Peon

Wishtoyo Foundation

Traditional and Other Chumash Stories

The Chumash are a Native American people who historically inhabited the central and southern coastal regions of California, in portions of what is now San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Ventura and Los Angeles Counties, extending from Morro Bay in the north to Malibu in the south. They also occupied three of the Channel Islands: Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel; the smaller island of Anacapa was likely inhabited on a seasonal basis due to the lack of a consistent water source.

Modern place names with Chumash origins include Malibu, Lompoc, Ojai, Pismo Beach, Point Mugu, Port Hueneme, Piru, Lake Castaic, Saticoy, and Simi Valley. Archaeological research demonstrates that the Chumash have deep roots in the Santa Barbara Channel area and lived along the southern California coast for millennia.

Indigenous peoples have lived along the California coast for at least 11,000 years or since 7000 BC.Sites of the Millingstone Horizon date from 7000 to 4500 BC and show evidence of a subsistence system focused on the processing of seeds with metates and manos. During that time, people used bipointed bone objects and line to catch fish and began making beads from shells of the marine olive snail (Olivella biplicata). The name Chumash means “bead maker” or “seashell people” being that they originated near the Santa Barbara coast. The Chumash tribes near the coast benefited most with the “close juxtaposition of a variety or marine and terrestrial habitats, intensive upwelling in coastal waters, and intentional burning of the landscape made the Santa Barbara Channel region one of the most resource abundant places on the planet.”

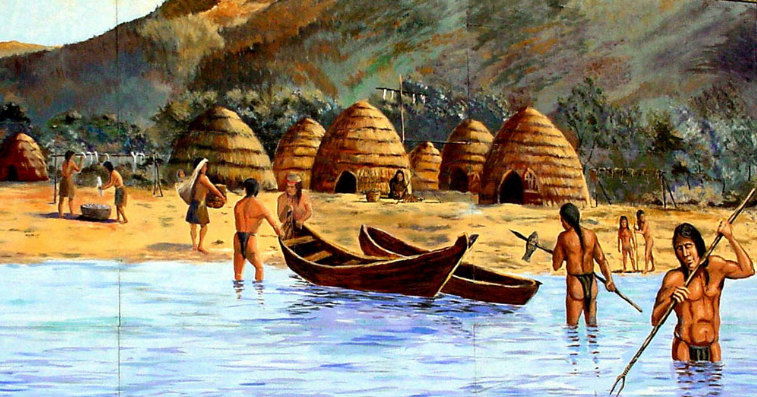

While droughts were not uncommon in the centuries of the first millennium AD, a population explosion occurred with the coming of the medieval warm period. “Marine productivity soared between 950 and 1300 as natural upwelling intensified off the coast.” Before the mission period, the Chumash lived in over 150 independent villages, speaking variations of the same language. Much of their culture consisted of basketry, bead manufacturing and trading, cuisine of local abalone and clam, herbalism which consisted of using local herbs to produce teas and medical reliefs, rock art, and the scorpion tree. The scorpion tree was significant to the Chumash as shown in its arborglyph: a carving depicting a six-legged creature with a headdress including a crown and two spheres. The shamans participated in the carving which was used in observations of the stars and in part of the Chumash calendar.

The Chumash resided between the Santa Ynez Mountains and the California coasts where a bounty of resources could be found. The tribe lived in an area of three environments: the interior, the coast, and the Northern Channel Islands. The interior is composed of the land outside the coast and spanning the wide plains, rivers, and mountains. The coast covers the cliffs, land close to the ocean, and the areas of the ocean from which the Chumash harvested. The Northern Channel Islands lie off the coast of the Chumash territory. All of the California coastal-interior has a Mediterranean climate due to the incoming ocean winds.

Precontact distribution of the Chumash

The mild temperatures, save for winter, made gathering easy; during the cold months, the Chumash harvested what they could and supplemented their diets with stored foods. What villagers gathered and traded during the seasons changed depending on where they resided. With coasts populated by masses of species of fish and land densely covered by trees and animals, the Chumash had a diverse array of food. Abundant resources and a winter rarely harsh enough to cause concern meant the tribe lived a sedentary lifestyle in addition to a subsistence existence. Villages in the three aforementioned areas contained remains of sea mammals, indicating that trade networks existed for moving materials throughout the Chumash territory.

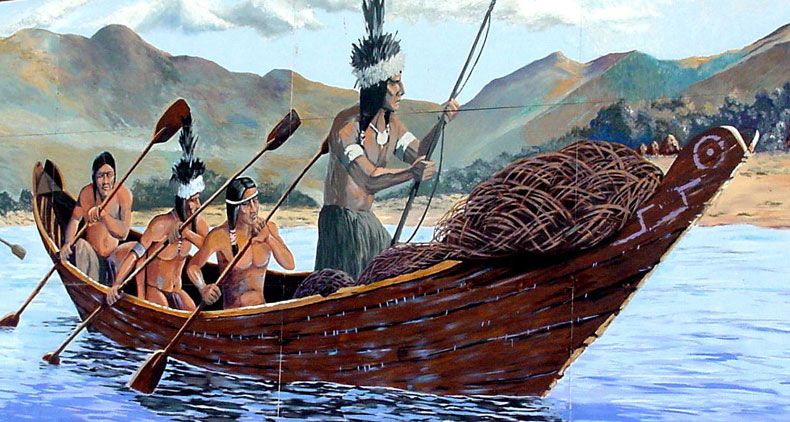

The closer a village was to the ocean, the greater its reliance on maritime resources. Due to advanced canoe designs, coastal and island people could procure fish and aquatic mammals from farther out. Shellfish were a good source of nutrition: relatively easy to find and abundant. Many of the favored varieties grew in tidal zones. Shellfish grew in abundance during winter to early spring; their proximity to shore made collection easier. Some of the consumed species included mussels, abalone, and a wide array of clams. Haliotis rufescens (red abalone) was harvested along the Central California coast in the pre-contact era. The Chumash and other California Indians also used red abalone shells to make a variety of fishhooks, beads, ornaments, and other artifacts.

Ocean animals such as otters and seals were thought to be the primary meal of coastal tribes people, but recent evidence shows the aforementioned trade networks exchanged oceanic animals for terrestrial foods from the interior. Any village could acquire fish, but the coastal and island communities specialized in catching not just smaller fish, but also the massive catches such as swordfish. This feat, difficult even for today’s technology, was made possible by the tomol plank canoe. Its design allowed for the capture of deepwater fish, and it facilitated trade routes between villages.

Some researchers believe that the Chumash may have been visited by Polynesians between AD 400 and 800, nearly 1,000 years before Christopher Columbus reached the Americas. The Chumash advanced sewn-plank canoe design, used throughout the Polynesian Islands but unknown in North America except by those two tribes, is cited as the chief evidence for contact. Comparative linguistics may provide evidence as the Chumash word for “sewn-plank canoe”, tomolo’o, may have been derived from kumula’au, the Polynesian word for the redwood logs used in that construction. However, the language comparison is generally considered tentative. Furthermore, the development of the Chumash plank canoe is fairly well represented in the archaeological record and spans several centuries. The concept is rejected by most archaeologists who work with the Chumash culture, and there is no evidence of a genetic legacy.

Before contact with Europeans, coastal Chumash relied less on terrestrial resources than they did on maritime; vice versa for interior Chumash. Regardless, they consumed similar land resources. Like many other tribes, deer were the most important land mammal the Chumash pursued; deer were consumed in varying amounts across all regions, which cannot be said for other terrestrial animals. Interior Chumash placed greater value on the deer, to the extent that they had unique hunting practices for them. They dressed as deer and grazed alongside the animals until the hunters were in range to use their arrows.Even Chumash close to the ocean pursued deer, though in understandably fewer numbers, and what more meat the villages needed they acquired from smaller animals such as rabbits and birds. Plant foods composed the rest of Chumash diet, especially acorns, which were the staple food despite the work needed to remove their inherent toxins. They could be ground into a paste that was easy to eat and store for years.[26] Coast live oak provided the best acorns; their mush would be served usually unseasoned with meat and/or fish.