DISAPPEARING WORLD OF THE KALASHA

ADDITIONAL VIDEOS OF THE KALASH PEOPLE

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF PAKISTAN

A HISTORICAL REFLECTION OF ZHOSHI: THE SPRING FESTIVAL OF THE KALASHA OF CHITRAL

Real generosity means doing good for someone who may never find out. You will be known by what you give to the world, not for what you earn. In the words of Khalil Gibran: “Generosity is giving more than you can, and pride is taking less than you need.” Treat everyone, and I mean everyone, with kindness, not necessarily because they are nice, but because you are. The unwritten law of prosperity is generosity – if you want more, give more, for it is in giving that we receive. Remember, that the happiest people are not those getting more, but those giving more. We should also realise that giving is not just about making a donation. It’s about making a difference. Money is but one avenue for generosity. Kindness is an even more valuable currency. At the end of the day, a generous heart, kind speech, and a life of service and compassion are the things that really renew humanity. Make sure your children play and make friends with underprivileged kids. The world will be a beautiful place tomorrow. Don’t be impressed by wealth, followers, degrees, and other titles. Be impressed by kindness, integrity, humility, and generosity.

Remember: if you have more than you need, bless someone else who has less. When God blesses you financially, don’t raise your standard of living; raise your standard of giving. And, remember, you do not have to be rich to be generous. Every kind act, even a small one, is a generous act. Giving is not a debt you owe. It’s a seed you sow!!

I wish you a very Good Morning. Be generous today.

A bill for the protection of minorities rights was presented in the SenateIslamabad. Muslim League N Senator Javed Abbasi presented a bill for the protection of minorities rights at the Senate session. The bill said hatred and insulting against religious minorities will not be part of the educational curriculum. The forced religious minorities change will be prohibited. The rights of the K The bill said that the government will provide protection and assistance to the person who is affected by forced religion change. The person who forced religion change will be sentenced to 7 years in prison and up to one lakh rupees. According to the bill, there will be a prohibition of interreligious marriage. Interreligious minority of the lesser age religious minority Addy Forced marriage will be imagined and forced marriage will be cancelled. Those who marry a minor religious minority will be sentenced to 10 years imprisonment and a fine of Rs 5 lakh as a punishment. Similarly, a person who marry a religious minority will be imprisoned for 14 years and 5 lakh rupees fine. Bil M It’s clear It was said that religious minorities will have the right to live with freedom. For a hateful crime against religious minorities, there will be 3 years imprisonment and 50 thousand rupees fine. According to the bill, the perpetrator of the crime of violence against religious minorities will be sentenced to 3 years and fifty thousand fine, the religious minorities have been formed Ed The perpetrator will be sentenced to one year and a fine of 25 thousand rupees. The bill presented in the Senate further says that the government will protect the religious assets of religious minorities. Those who harm the religious assets of the politicians will be sentenced to 7 years in prison and 50 thousand rupees fine. In the A-Bal It has been said that all crimes against religious minorities will be unbailable.

Redemption of walnut trees in Chitral sought

CHITRAL: “All the seven trees didn’t belong to me. Instead, they were purchased long ago by Muslims from downhill valleys,” insisted Gabu Jan Kalash pointing towards the towering walnut trees in front of his small house.The signs of dislike and annoyance towards the tree owners were clear from the face of the Kalash elder, who was in his 80s.This was not single in the Kalash valley of Bumburate but this was a common issue of the three valleys of the ancient people (Kalash) to have walnut trees, which were owned by outsiders.

Pointing towards one of the trees, Mr. Gabu Jan said it was purchased by an outsider in lieu of an old blanket from his late father while he (Jan) was teenager at that time.He said the Kalash people suffered from abject poverty and therefore, they used to sell their trees at throwaway prices to outsiders, who currently owned more than half of the old walnut trees in the valley.“Former prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had started giving us back our trees after paying outsiders a large sum of money. However, it all ended after his government was over,” he said.It was in 1975 that on the demand of the local people, the then prime minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto had ordered to redeem the walnut trees from the outsiders and return them to their real owners so that they could be strengthened financially.

The plan was discontinued later on when Martial Law imposed on the country. A retired official of the revenue department, Khosh Mohammad, said in 1980, the walnut tree redemption plan was revived due to the personal interest of then deputy commissioner Chitral Shakil Durrani. He said with the meagre allocations for the plan, tens of families were able to redeem their walnut trees. “Former president Pervez Musharraf restarted the process when he visited the valley but it was discontinued very soon. Few villages had benefited from the initiative,” he said.The former official said walnut trees in Kalash valleys formed the major source of income due to the high rising prices of walnut in the market and three to four trees of walnut were enough to be a source of sustenance for a Kalash family which necessitated their redemption from outsiders to wipe out abject poverty.

Wazir Zada Kalash, a young educated person from Bumburate valley, said walnut trees standing on the fields hampered the growth of the crop grown on it, while no fresh sapling could be planted beneath the old trees.“ A Kalash will have to wait for 120 years as a walnut tree takes such a length of time and it will take half a century more to see the Kalash valleys free from the mortgaged trees of walnut owned by the outsiders,” he said. He said with the advent of modern times and prosperity in the valley, the sale of walnut trees had discontinued. The youngster said an endowment fund should be established for immediately redeeming the mortgaged walnut trees of Kalash from outsiders. When contacted, Chitral deputy commissioner Osama Ahmed Warraich expressed ignorance about the matter.He said he was posted to the district recently and was engaged in disaster management so he didn’t get a chance to look into the matter.

Published in Dawn, July 9th, 2016

Taleno/Thumishalling Festival celebrated in Khanabad Hunza

Taleno/Thumishalling Festival celebrated in Khanabad Hunza.Taleno is celebrated on 21st December every year. On that night the people gather in common places to burn “Shri Badat”-an ancient cannibal king of Gilgit.The story behind this ritual is that Shiribadat was considered to be taking a human as his meal. The people believe that every year it is complementary to burn the evil spirit of Shiribadat otherwise he may wake up again and will be dangerous for the people and all living beings of valley.

Kalash winter solstice festival 22 dec 2021

Interview conducted during the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

Kalash winter festival episode 2

Astore markhor fighting for female in rut season | Gilgit Baltistan

Help Preserve Kalash a tribe in Pakistan for United Nations Protected site

Kalash Art & Thumri Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan

Khowar Song (Shuja Ul Haq and Basharat Basha)

The decade following the Egyptian cotton boom, a report following an expedition to Afghanistan in the 1870s noted:

The territory between Afghanistan and British India was demarcated between 1894 and 1896. Part of the frontier lying between Nawa Kotal in the outskirts of Mohmand country and Bashgal Valley on the outskirts of Kafiristan was demarcated by 1895 in an agreement reached on 9 April 1895. Abdur Rahman wanted to force every community and tribal confederation to accept his single interpretation of Islam due to it being the only uniting factor. After the subjugation of Hazaras, Kafiristan was the last remaining autonomous part.

Emir Abdur Rahman Khan’s forces invaded Kafiristan in the winter of 1895–96 and captured it in 40 days according to his autobiography. Columns invaded it from the west through Panjshir to Kullum, the strongest fort of the region. The columns from the north came through Badakhshan and from the east through Asmar. A small column also came from south-west through Laghman. The Kafirs were resettled in Laghman while the region was settled by veteran soldiers and other Afghans. The Kafirs were converted and some also converted to avoid the jizya.

A few years after Robertson’s visit, in 1895–96, Amir Abdur Rahman Khan invaded and converted the Kafirs to Islam as a symbolic climax to his campaigns to bring the country under a centralised Afghan government. He had similarly subjugated the Hazara people in 1892–93. In 1896 Abdur Rahman Khan, who had thus conquered the region for Islam, renamed the people the Nuristani (“Enlightened Ones” in Persian) and the land as Nuristan (“Land of the Enlightened”).

Kafiristan was full of steep and wooded valleys. It was famous for its precise wood carving, especially of cedar-wood pillars, carved doors, furniture (including “horn chairs“) and statuary. Some of these pillars survive, as they were reused in mosques, but temples, shrines, and centers of local cults, with their wooden effigies and multitudes of ancestor figures were torched and burnt to the ground. Only a small fraction brought back to Kabul as spoils of this Islamic victory over infidels. These consisted of various wooden effigies of ancestral heroes and pre-Islamic commemorative chairs. Of the more than thirty wooden figures brought to Kabul in 1896 or shortly thereafter, fourteen went to the Kabul Museum and four to the Musée Guimet and the Musée de l’Homme located in Paris. Those in the Kabul Museum were badly damaged under the Taliban but have since been restored.

A few hundred Kati Kafirs, known as the “Red Kafirs” of the Bashgal Valley, fled across the border into Chitral but, uprooted from their homeland, they converted by the 1930s. They settled near the frontier in the valleys of Rumbur, Bumboret and Urtsun, which were then inhabited by the Kalasha tribe or the Black Kafirs. Only this group in the five valleys of Birir, Bumburet, Rumbur, Jineret and Urtsun escaped conversion, because they were located east of the Durand Line in the princely state of Chitral. However, by the 1940s the southern valleys of Urtsun and Jingeret had been converted. After a decline in population caused by forced conversion in the 1970s, this region of Kafiristan in Pakistan, known as Kalasha Desh, has recently shown an increase in its population.

In early 1991, the Republic of Afghanistan government recognized the de facto autonomy of Nuristan and created a new province of that name from districts of Kunar Province and Lamghan Province.

“I dedicate this page to my good friend, M. Bugi, his family, and to the Kalash people (‘mountain people’) high up in the Himalaya Mountains..”

http://www.indigenouspeople.net/chitral.htm

http://indigenouspeople.net/Help/

https://www.indigenouspeople.net/Pakistan.pdf

https://www.indigenouspeople.net/KalashBrochure.pdf

https://www.indigenouspeople.net/Kalashdictionary.pdf

https://www.indigenouspeople.net/kalash.pdf

https://www.indigenouspeople.net/bugi.htm

https://www.indigenouspeople.net/journey.htm

http://www.indigenouspeople.net/lahore.htm

http://www.indigenouspeople.net/newKalash/

“Brargini, doy tazim”

(Brothers, he will give thanks.)

HISTORY OF THE KALASH

KALASH BLOG

Lakshan Bibi speaking at the

UN regarding global warming

May 22, 2007

ARTICLES

A Little Boy Said to His Mother

A Vanishing Way of Life

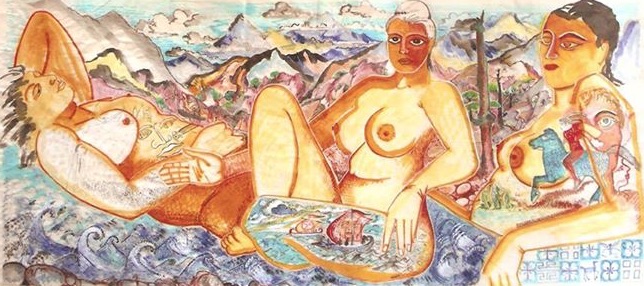

Bugi combines tradition and surrealism

Kalasha Peoples Call for Cultural Survival

Two-week Kalash festival kicks off

MAIN MENU

Chinese Calligraphy

by Lee Shouping

Mahraka.com

A Website on the Culture,

History and Languages of Chitral.

The Kalash or Kalasha, are an ethnic group found in the Hindu Kush mountain range in the Chitral district of the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan. Although quite numerous before the twentieth century, this non-Muslim group has been partially assimilated by the larger Muslim majority of Pakistan and seen its numbers dwindle over the past century. Today, sheikhs, or converts to Islam, make up more than half of the total Kalasha-speaking population.

The culture of Kalash people is unique and differs drastically from the various ethnic groups surrounding them. They are polytheists and nature plays a highly significant and spiritual role in their daily life. As part of their religious tradition, sacrifices are offered and festivals held to give thanks for the abundant resources of their three valleys. Kalash mythology and folklore has been compared to that of ancient Greece, but they are much closer to Indo-Iranian (Vedic and pre-Zoroastrian) traditions.

Wonderful To Pay Tributes to HISTORY, and there is No shame in admitting that Great Artists have Influenced me, Instead of Finding Easy routes for fame Fortune and Glory I LOVE my Teachers, as i call Myself a Student of History,lots of My works are There, to support one of Its Kind, he is a Master, Jamil Naqsh Was My Teacher in Pakistan, as well as Father of Danish Azar Zuby I learnt a Lot from Them,,as well as Multiple images Of Surrealism, Hieronymus Bosch the GREAT Master, and Of Course what u see here Is REMBRANDT-

Words Of Johanna from USA, half Greek Half American-(QUOTE). For several years now, i have been privileged to be a part of a movement in acknowledgment of Kalash and indigenous tribes by our dear one, MBugi….the incorporation of Mr. Wajid’s choice of music enhances the beautiful/loving paintings MBugi presents to us; his love for people around the world is more than inspiring, it is uplifting! He encourages w/out his knowing….touches heart strings so deeply that one is lead to follow such a person so dedicated. MBugi’s ability to coordinate and make possible to all the works of his lifetime. Most assuredly, he has and will leave such a legacy. I as well, include the children; who are our future. The children who come to us to learn with desire and he makes it possible for them to exhibit their feelings/emotions in to art in the finest ways. All who observe, come in to contact w/him are included in his tributes to his people of Pakistan. It IS humbling when after so many years he continues

INNOVATIONS OF REMBRANDT

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn, who many consider the greatest artist of all time, learned all that was then known about oil painting while still a very young man, surpassing his teachers very early in his career, and then proceeded to add his own discoveries to the technical knowledge of his time. To this day Rembrandt’s best works remain unsurpassed, and serve as inspiration to those of us who paint. This being the case, any book on advanced techniques must address Rembrandt separately and at such length as the author’s knowledge allows. What technical information Rembrandt was taught may be discerned by studying the works of his instructors, Jacob Isaacxszoon Van Swanenburch and Pieter Lastmann. Such study also immediately shows the genius of Rembrandt by the extent to which he so obviously surpassed them both, and by how early in his career he did so. Nonetheless, his training under them was an important factor in his artistic development,

Nonetheless, his training under them was an important factor in his artistic development, and should not be minimized, as both teachers seem to have possessed a working knowledge of the painting methods in use at that time. Various examples of Rembrandt’s work show that he was not limited to any one technique, but employed them all, the choice depending on which approach best suited the subject in question, and for what purpose the painting was intended. His facility with all three of the aforementioned methods of painting soon led him to combine aspects of one with another, and to add innovations of his own.

*Sitarist is Nikhil Banerjee Raag Darbari *–

and I hope that you Will Write some thing please, as After the Petition is Finished i shall Continue for Promotion of Arts In Pakistan,__/\__

Vir Kashmiri ……..quote,…….infatuating the lingering music in the background is gripping…..its still running…..

Vir Kashmiri ……..Bugi ji you are sheer joy thank you greatly for your presence…

MBugi

It took me 40 Long Years to Compile Work as well as Collect These Images, and Syed Wajid Based in Dubai Chose and Gave structure to My Ideas, as Great Master and His association with Mughals was Attributed, Most Of the Western Press Hides his Copies for it Brings Prejudice against Him,, Copying Masters,I also Got a Cold Shoulder from Rembrandt Museum In Amsterdam—I carried On Regardless, RESULT is Here, Specially The last Letter from National College Of Arts Now we will Try to work On *FAIZ AMAN MELA* The Chitralis are still speaking today one of the oldest Indo-European languages in a relatively undiluted form. This is not surprising in view of the remoteness of their area. They are so far up in the Hindu Kush mountains that it would be almost impossible for an invader to conquer them. By far the lowest pass into Chitral is Lowari Top, which is over 10,000 feet high, too high for an invading army easily to cross. The path up the Kunar river from Jalalabad becomes so narrow below Ashret that no invading army has ever tried it. There have been several attempts to invade Chitral within relatively modern historical times. One group came across Boroghol Pass, were defeated and went back. Another group came across Urtsun Pass. The British in 1895 simultaneously came across Shandur Pass and Lowari Top in a mission to rescue a group British hostages which had been taken. They conquered the area, which is the reason why Chitral is now part of Pakistan.

The world’s highest polo playground is located here. It is surrounded by some of the most spectacular mountains in the world. The history of this annual polo tournament at the Shandur Top dates back to 1936 when a British Political Agent, Major Cobb organised the first polo tournament here. Major Cobb was fond of playing polo under full moon and he developed a polo ground near Shandur that was named after him and is still known as ‘Major Cobb Moony Polo Ground’. Polo fans gather at Shandur from all over the world to participate in the spectacular polo events during this tournament.

Mainland Pakistan refers to the people of Punjab, Sindh and Peshawar. The Kalash people and their way of life are being destroyed by tourism like this.

Modern progress should never be used at the expense of any peoples culture.

Please contact M. Bugi at:

to do all we can to prevent this cultural loss.

The Kalash people will be forever grateful for all of your support!

Burushaski Song and Images of my adopted Kalash families, from MBugi Bugi Bugiandassociates.

Thank you. I hope that you will remember The Silk-Route is full of Poets, Stories and Songs:

Travelled from heart to heart before the actual writing were written,

I am very proud of the area, although I am not from there.

This is one of the best films I have seen about the Kalash and the people of the area of Chitral, Nager, Hunza.

In this small region more then 10 ancient Languages are spoken and the anthropologists are puzzled.

Mr George Morgersterine from Norway wrote in 1935 that the area has no parallel to other areas in the whole world,

with such richness in culture and so strong in history.

The Kalash or Kalasha, are an ethnic group found in the Hindu Kush mountain range in the Chitral district of the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan. Although quite numerous before the twentieth century, this non-Muslim group has been partially assimilated by the larger Muslim majority of Pakistan and seen its numbers dwindle over the past century. Today, sheikhs, or converts to Islam, make up more than half of the total Kalasha-speaking population. The culture of Kalash people is unique and differs drastically from the various ethnic groups surrounding them. They are polytheists and nature plays a highly significant and spiritual role in their daily life. As part of their religious tradition, sacrifices are offered and festivals held to give thanks for the abundant resources of their three valleys. Kalash mythology and folklore has been compared to that of ancient Greece, but they are much closer to Indo-Iranian (Vedic and pre-Zoroastrian) traditions.

The Chitralis are still speaking today one of the oldest Indo-European languages in a relatively undiluted form. This is not surprising in view of the remoteness of their area. They are so far up in the Hindu Kush mountains that it would be almost impossible for an invader to conquer them. By far the lowest pass into Chitral is Lowari Top, which is over 10,000 feet high, too high for an invading army easily to cross. The path up the Kunar river from Jalalabad becomes so narrow below Ashret that no invading army has ever tried it. There have been several attempts to invade Chitral within relatively modern historical times. One group came across Boroghol Pass, were defeated and went back. Another group came across Urtsun Pass. The British in 1895 simultaneously came across Shandur Pass and Lowari Top in a mission to rescue a group British hostages which had been taken. They conquered the area, which is the reason why Chitral is now part of Pakistan.

The world’s highest polo playground is located here. It is surrounded by some of the most spectacular mountains in the world. The history of this annual polo tournament at the Shandur Top dates back to 1936 when a British Political Agent, Major Cobb organised the first polo tournament here. Major Cobb was fond of playing polo under full moon and he developed a polo ground near Shandur that was named after him and is still known as ‘Major Cobb Moony Polo Ground’. Polo fans gather at Shandur from all over the world to participate in the spectacular polo events during this tournament.

The Kalash were ruled by the Mehtar of Chitral from the 1700s onward. They have enjoyed a cordial relationship with the major ethnic group of Chitral, the Kho who are Sunni and Ismaili Muslims. The multi-ethnic and multi-religious State of Chitral ensured that the Kalash were able to live in peace and harmony and practice their culture and religion. The Nuristani, their neighbors in the region of former Kafiristan west of the border, were invaded in the 1890s and converted to Islam by Amir Abdur-Rahman of Afghanistan and their land was renamed Nuristan.

Prior to that event, the people of Kafiristan had paid tribute to the Mehtar of Chitral and accepted his suzerainty. This came to an end with the Durand Agreement when Kafiristan fell under the Afghan sphere of Influence. Recently, the Kalash have been able to stop their demographic and cultural spiral towards extinction and have, for the past 30 years, been on the rebound. Increased international awareness, a more tolerant government, and monetary assistance has allowed them to continue their way of life. Their numbers remain stable at around 3,000. Although many convert to Islam, the high birth rate replaces them, and with medical facilities (previously there were none) they live longer.

Allegations of “immorality” connected with their practices have led to the forcible conversion to Islam of several villages in the 1950s, which has led to heightened antagonism between the Kalash and the surrounding Muslims. Since the 1970s, schools and roads were built in some valleys.

Khowar is the language of the Kalash tribe, spoken in Chitral, which is in the far Northwest corner of Pakistan; a beautiful valley in the Hindukush range of Mountains. Khowar is classified as an Indo-European language of the Dardic Group. However, only Kalashamun is closely related to Khowar. It is spoken as the primary language by 250,000 people in Chitral. There are also pockets of speakers in Gilgit. It is clear that the current Chitralis have lived in their mountain home for 3,000 to 4,000 years.The people of Chitral are called Kho. Traditionally they are peaceful and law abiding citizens.

Khowar has 42 phonemes. Several of these are not found in any other language of the region. The letters /t/, /th/, /d/, /l/, /sh/, /ch/, /chh/, and /j/ all have two different forms, one retroflexed and the other dential-veolar non-retroflexed. Every Chitrali who learned the language on his mother’s knee can readily distinguish these forms, whereas others can never learn them, regardless of how long they have lived in Chitral.

Khowar does not have a written form in common use. Before 1947, written communications in Chitral were in Farsi, which explains the large number of Farsi loan words. Today, written communications are in Urdu. Several attempts have been made to introduce a Urdu or Roman based writing script into Khowar, but these have never gained widespread acceptance.

Alexander the Great encountered them when he visited the area. The proof of this is that in the histories of Alexander the Great it is written that he encountered strange wooden boxes, which his troops chopped up to be used as firewood. These “boxes” were actually coffins for their dead following the custom which the Kalash Kafirs of Chitral still have of leaving their dead outside in wooden coffins. He also described them as a light skinned race of European type people, which is exactly what they are. This further proves that the same people were there then as are there now.

The Kalash Kafir religion which is still practiced today by about 3,000 people in Chitral has a resemblance to the ancient Greek religion of gods and goddesses. This has led some to speculate that the Kalash got their religion from the invading Greeks. This is unlikely. The Greeks merely passed through in 327 B.C., probably within 50 miles of Chitral, but did not enter Chitral itself and did not stop or stay for long. What is likely is that the Kalash religion and the Greek religion have a common origin. Both came from some proto-Indo European religion which was carried along with the Indo European language when the Chitralis first got there some 3,000 to 4,000 years ago.

SONGS / MUSIC

The above video contains Yoorman Hamin

sung by Mir Wali, a famous Chitrali singer

“YOORMAN HAMIN”

composed by Baba Siyar,

a Chitrali poet and mystic

I roam on the mountains as if I trod on hot ashes,

The sword of love has stricken me;

I made of my self a shield of two bones.

Oh Yoorman Hamin!

Oh Fairy I swear by God after seeing you there is no light,

Night and day are alike dark to me, no dawn comes to me.

Oh Yoorman Hamin!

The curls of my bulbul are like rosebuds and maiden hair fern,

Come sit by me and sing like a mynah or a bulbul.

Oh Yoorman Hamin!

Still I look at you; you turn away and look else where,

My life is yours, why do look at my enemies?

Oh Yoorman Hamin

Your long ringlets and your well-curled hair are like bedmushk

You bind up your locks to slay this lad.

Oh Yoorman Hamin

I sigh day and night for the bulbul,

I kiss your pearly ringlets in my dreams.

Oh Yoorman Hamin

Translated into English by

Colonel Jhon Biddulph in 1876

BURUSHASKI SONG AND TRANSLATION

Un’e shule men fana o mannan unar begolel

Some one is longing for your love, but you don’t know.

Men ashiq’ye zamun shuchan unar begolel

Some one is suffering in your love, but you don’t know.

Khushba akuman fikerenge tufano lo chapba

Don’t think that I’m glad, I am in storm of woes.

Berum un’e yadlo heraba unar begolel

How much I have cried in your love, but you don’t know.

Hal satsumu arama pe ya thapmo dang api

I am left with charmless days and sleepless nights.

Mu belate ja ase hun nebela unar begolel

Now my heart is dying, but you don’t know

Shahid shule maidano lo but chor qadam o sa

Shahid, you have stepped into the world of love too early.

Khot ishqe gamish besan bela unar begolel unar begolel

The aftermath of love, you don’t know you don’t know.

(Translated into English by Zahid Hussain Kanjuti)

Krathiman krathiman may ruaw tu i

Smiling (or laughing),smiling (or laughing) come before me

Dras’ni mastrukas barabar una i

Come, appear with the rising moon

Ashek hardi khoji bazarai paraw

Love–sick heart went searching in the bazar

May zindagi tay intazarai paraw

My life disappeared, waiting for you

Ko paraw ko paraw

Why did it go? why did it go?

Kal’as’a deshaw bus’bira

Mature male goat from the Kalasha valleys

Talim K.Z. ghon’ zhe nat’ kariu day

Talim K.Z. is singing and dancingMessage with it to you:

Kal’as’a mutibus’ T.K Bazik,

Kalasha …….male goat T.K. Bazik

gho’n’ nyiay asau ne bhai dorik,

He has got the song out, not able to wait

ne bhai hardi trupai shiau troik,

Not being able, his heart hurts, (we) will weep

ghon’ zhe nat’ kai asau, kia dunik?

He has made a song and a dance, what are we to think?

shama jagaa phato maa zhe matrik

Watch this then read it and (we)will say it aloud

khosh mimi hiu e…gheri pashik.

Do you all like it ? See you again.

The Chitralis are still speaking today one of the oldest Indo-European languages in a relatively undiluted form. This is not surprising in view of the remoteness of their area. They are so far up in the Hindu Kush mountains that it would be almost impossible for an invader to conquer them. By far the lowest pass into Chitral is Lowari Top, which is over 10,000 feet high, too high for an invading army easily to cross. The path up the Kunar river from Jalalabad becomes so narrow below Ashret that no invading army has ever tried it. There have been several attempts to invade Chitral within relatively modern historical times. One group came across Boroghol Pass, were defeated and went back. Another group came across Urtsun Pass.

“Un’e shule men fana o mannan unar begolel.

(Some one is longing for your love, but you don’t know.)”

The Chitralis are still speaking today one of the oldest Indo-European languages in a relatively undiluted form. This is not surprising in view of the remoteness of their area. They are so far up in the Hindu Kush mountains that it would be almost impossible for an invader to conquer them. By far the lowest pass into Chitral is Lowari Top, which is over 10,000 feet high, too high for an invading army easily to cross. The path up the Kunar river from Jalalabad becomes so narrow below Ashret that no invading army has ever tried it. There have been several attempts to invade Chitral within relatively modern historical times. One group came across Boroghol Pass, were defeated and went back. Another group came across Urtsun Pass. The British in 1895 simultaneously came across Shandur Pass and Lowari Top in a mission to rescue a group British hostages which had been taken. They conquered the area, which is the reason why Chitral is now part of Pakistan.

The world’s highest polo playground is located here. It is surrounded by some of the most spectacular mountains in the world. The history of this annual polo tournament at the Shandur Top dates back to 1936 when a British Political Agent, Major Cobb organised the first polo tournament here. Major Cobb was fond of playing polo under full moon and he developed a polo ground near Shandur that was named after him and is still known as ‘Major Cobb Moony Polo Ground’. Polo fans gather at Shandur from all over the world to participate in the spectacular polo events during this tournament.

ASSAULT ON THE INDIGENOUS

KALASH PEOPLE OF CHITRAL, PAKISTAN

Dear Friends:

We the Indigenous Kalash people of Chitral are under siege due to the

onslaught of tourism and hotel businesses. The Pakistan Tourism

Development Corporation (PTOC), along with Pakistan Internation

Airlines (PIA), are both corporations that are using the Kalash people

as free commercial material to promote tourist

business around the world.

The numbers of tourists are increasing every year, making our lives

miserable; however, the assault does not stop here. The rich businessmen

from mainland Pakistan* saw the tourism potential. They began to

build hotel/motels in the tiny Kalash valley by taking over the

indigenous people’s lands. The hotel owners cut down the orchards

and dismantled sacred landmarks of the Kalash people for hotel/motel sites.

The hotels are contaminating the potable water, polluting the Kalash

valleys with empty cans, bottles, broken glass, and plastic waste left

behind by the tourists in the hotels. The Kalash valleys are tiny and

there is no place to dump the refuse, so hotel owners are dumping the

garbage into the drinking water, which comes from glacial melting.

The tremendous pressure from the tourists upon the Kalash people is

unbearable, but the worst part is played out by the inconsiderate mainland

Pakistani hotel owners who have put irreversible, deterioratmg effects

on the Kalash environment!

Food, fuel, firewood and other daily necessities are becoming scarce

to our people, due to big buying demands from the hotel owners.

The prices of commodities have risen considerably, bringing hardship

upon the indigenous people. Cameras aiming at them, the tourists jump out

of jeeps and turn the peacful valley into a zoo. It is becoming almost

impossible for us to keep our identity, traditions, and values intact,

which we have done for thousands of years. The Indigenous Kalash people

are on the brink of extinction, due to the constant onslaught of tourists

and greedy hotel owners from Pakistan.

We, the Kalash people, appeal to the you, our indigenous brothers and

sisters, and all people worldwide, for your help. Please appeal to the Pakistani

government to help us remove these hotels from our midst.

We also appeal to the PTDC hotel and all tour guides to advise tourists

to boycott these hotels and help us to return the valley of Chitral

to their rightful owners, the Kalash people!

A Little Boy Said to His Mother

Every picture tells its story.,

The leaves falling from the tree

Down into the same tree

Being reflected in the river.

If you can make fire out of wood, you can also make pictures, carve a wooden flame, make art. `And so, Bugi’s craft was born in being realised.

Throughout his formative years, Bugi introduced himself, and was introduced, thought books, to Oriental Minatures and Eastern Woodprints. Born and raised in Lahore, Bugi was surrounded by objects steeped in tradition. He grew interested in the Kalash; an indigenous minority peopleing part of North Pakistan and Afghastan. Their art forms enthralled me, their wood and rock carvings. These carvings were sculpted by shepards marking the route of the silk trade from China, eastwards. In woodcarvings I felt the roots of trees. Through wood I touched my forefathers, felt the tree in myself, wished to maintain tradition.’

When Bugi was nineteen he went to the Soviet culture center in Karachi, where he discovered books on the great western artists. Names such as Jeryonomous Den Bosch and Michael Angelo entered his vison literally and aesthically. In his own words, first came wood, then paint; that sort of evolution.’

For the next fifteen years, Bugi worked for advertising agencies, where he developed, through graphics, a modern perception of visual expression. Eventually, the trough was full. Overspill. Bugi quit. He wanted to travel, to touch, sniff and breath other cultures. He went round the world twice, touching its four corners. Although the world is round, the eye has a corner. During his travels, Bugi felt the imponderable. Light takes those corners away, he says, filling the broad room of his smile.

In China he met and worked under Li Shou Ping in Guilin. Li was a fine landscape painter, who made Bugi sit on the floor, thus introducing him to the first position of traditional Chinese painting. The hand is the body. The hand in the body. The big before the small. Bugi had learned something. It was time to move on, leave the floor of the mountain and sail towards the unknown.

He arrived in Cuba after spending three and a half months in Indonesia. One day while walking in Santiago, Bugi saw a portrait of Che Guervera Lynch through the bars of a painless window. Who is the artist? he enquired. Roberto Gonzalez, his sister replied. She gave Bugi her brother’s address. Next day Bugi was on a bus heading for Matenza, where he made contact with Roberto and his acolytes. After spending four months in Cuba, Bugi, continuing his journey, arrived in Panama.

By the banks of the canal, he studied the technique of raising and lowering water levels. `The Mathmathics Of Sluice. Water finds its own level, sometimes with man’s assistance. Water and paint on canvas are no different. The two merge, flow as one, inseperatebly surfacing in the cornerless eye, like the fish in the canal coming up to the flood lights along its bank, coming up to dud-suns, dieing stars.

In New York, Bugi attended the museum of Modern Art and rediscovered surrealism. The man and his madness. A wooden flame will not burn unless lit From New York he travelled to New Orleans, Cajun Pie; then onto Norfolk Virginia…. O country roads take me home…then onto Paris and a dream come true; the history of impressionism, its colour and light; the ivy in the ditch not green but blue, the alder tree not brown, but pink; seeing things though, the endless eye looking at the finite, no corner cutting.

Now living in the Netherlands, where he attended art Academy, Bugi had been somewhat dryly and rationally seen as a…… Culture Dog…. Barking….Bow Wow…

which is a long winded way of saying, Bugi is a craftsman, no fly by night gimmick-merchant, not out to impress something upon the eye but to engrain it in the memory. His themse is loss, loss of tradition, cultural upheaval, the Kalash being a prime example. In fact, Bugi’s theme is life, what is not left of it, what has yet to be, the here, the now. His sense of loss is also the exile in himself attempting to find unconcealment. Through his travels, his study, his roots, Bugi paints and shapes his own peice of ground, far from home, to learn as Joyce says’ what the heart is and what it feels.

JOURNEY TO CHITRAL

Mirza and Habibullah go to Chitral to talk to the D.C., get permission to enter Kalash and check on horse food. Ayesha and I spend hours looking for anything for the horses to eat in Drosh. We walk through the fields trying to locate where wheat has been threshed so we can get some boose. We comb the bazaars for flour, barley, anything! Never thought we’d be so happy to find a sack of barley. The flies in the barren lot behind the hotel where the horses are staked are loathsome. The stench of their old bread and barley shit is nauseating.

The next morning we leave Drosh. Horse’s withers are bad. Coming down the Lowari Pass Shokot’s withers have started developing the same type of hard lump that Horse started with. Mirza rides Hercules, Ayesha rides Kodak, Habibullah and I walk leading Horse and Shokot.

We stop at an animal husbandry hospital on the outskirts of Drosh to see what can be done for the horses. The dispenser washes their wounds with the same orange wash we’ve been using, powders them with the same white mixture and has a boy bring out a bottle of oxytetracycline. There is only one shot left in the bottle. The rubber seal has already been punctured, but he plunges the dark green fluid into Horse’s neck.

The boy goes to the bazaar to bring more medicine. We have tea with the dispenser on the veranda. The liquid in the fresh bottle is a pale translucent amber color. He gives Shokot a shot. Mirza and Ayesha leave Drosh ponying Horse and Shokot. Habibullah and I remain to get supplies and hire a jeep to take us to Ayun. It’s enjoyable doing business in the bazaar with Habibullah. He does the bulk of the talking. No one knows I’m foreign. Just a couple of simple Pathans from down country. It’s nice not being the show for a change, just to relax in a part of it.

Habibullah and I hire a jeep to take us and the gear to Ayun. He will find another vehicle there, Insh’Allah, to take him on to Kafiristan. I plan to meet Mirza and Ayesha at the old suspension bridge that spans the river. We pass them on the road. An hour later I get off before where the bridge, built in 1927, crosses the muddy, rushing Kunar/Chitral River.

Beyond the bridge the road becomes dusty dirt on the west bank leading on to Ayun. It saves the distance of first riding to Chitral before backtracking to Ayun. Mirza had obtained our passes to enter Kafiristan when he went to Chitral with Habibullah. My job is to wait at the bridge to help them cross the four horses over. I sit on a grassy hillside overlooking the river with stream-lets of clear cool water gurgling through the short grass around me and tumbling down the rocky banks to join the swirling river. I smoke a cigarette and idly watch some grazing sheep.

Mirza, Ayesha and the horses arrive shortly after noon. Before crossing they join me on the grass for lunch—a can of sardines, crackers and water. Mirza wants to take pictures documenting our crossing of the suspension bridge but it is not to be. Before we can shoot anything a soldier comes up to us and tells us that it is illegal to photograph the bridge. He is an older fellow, approaching middle age and a potbelly, who could probably only be posted in such a useless post as guarding some stupid bridge (In all fairness we are right on the war sensitive Afghanistan border).

We show him our letters from Islamabad, first the English one to duly impress, then the Urdu one so he can read it. He’s rude. He doesn’t seem to be able to read Urdu very well though.

“We don’t give a shit about your stupid bridge, anyway,” I tell him. “We just want pictures of our horses crossing it. What importance can it have? It’s an antique. That is why we want the pictures.”

Mirza and I discuss shooting him but wisely decide just to head on. We still have a long, hot ride to Kafiristan and besides, bullets are costly.

After crossing the bridge I lead Horse. He is becoming lethargic and needs to be coaxed along. The bank of the river is rocky and 40 feet below us. The water is impossible to get to. In half an hour I decide to try to cadge a ride on the next jeep passing us to get into the valley of Kafiristan before the horses do, to make sure all arrangements are satisfactory.

Kafiristan (Kalash) is the home of the Kafir Kalash—primitive pagan tribes known as the Wearers of the Black Robes. Their origin is cloaked in controversy. Legend says that five soldiers from the legions of Alexander the Great settled there and are the progenitors of the Kalash.

They live in three valleys in small villages built on the hillsides near the banks of the Kalash River and its tiny tributaries in houses of rough hewn logs, double storied because of the steepness of the slopes. The lower portions are usually for animals and fodder storage for the long harsh winters. They practice a religion of nature worship. It is the only area in Pakistan or Afghanistan that hasn’t been converted to Islam, though that is slowly changing with the times. Across the mountains in Afghanistan the Kafirs were converted in the 1890s by Amir Abdur Rahman, the ‘Iron Amir’ of Kabul, and Kafiristan (land of unbelievers) became Nuristan (land of light).

Fifteen minutes after walking on ahead of Mirza and Ayesha, a jeep passes. It slows for me and I climb in. On the front seat sit two men along with the driver. The older of them, with a bushy, brown, wavy beard and wearing a pakul cap, asks me if I have heard of Rambur Valley. He tells me he is the headman of the village of Rambur. I vaguely remember him, but to my good luck, he doesn’t recognize me.

When he had last seen me two years ago I was speaking Farsi and English, not Pashtu. We had fought because I had defecated down by the river, which I hadn’t known at the time was their Kafir ‘holy place’. He had wanted me to wash in the river to rectify it but I wasn’t going to bathe in that icy water. I had told him the hell with him and his foolish Kafir superstitions. I promptly left and walked the 10 miles back to Bumburet!

We drive past the Kafiristan turnoff, a steep dirt road leading up and west into the narrow valley of Kafiristan. The jeep stops short of Ayun and I walk the remaining distance. Habibullah isn’t anywhere to be seen. I assume he has caught a jeep into Kafiristan and that everything will be prepared for our arrival.

I sit at a table set in the wide, dusty street with some chairs around it and a tattered canvas overhang to shield customers from the sun and drink mango sherbet with delightfully cold, dirty, shredded snow ice. Ayun is dead as it was on my last visit in 1987. It reminds me of a semi-deserted western ghost town. It is getting late in the day, almost 3:00 P.M., and there aren’t even any jeeps waiting around to go to Kafiristan. Not feeling too patient, I decide to start walking the distance. If a jeep comes there is only one road and I’ll be on it.

I head back down the road I had come into town on and make a sharp right turn up the dry, rocky, mountain pathway that leads to the Kafir valleys, winding back and forth up the mountain until I am high above the silvery Kalash River twisting through the valley below me on its way to join the Chitral River. At my feet is a steep incline of jumbled rocks tumbling chaotically down to green and golden fields of wheat nurtured on the life-giving crystal waters of the river, ripening in the warm summer winds. Good news, I think. Wheat is ripe and ready for the thresher. There will be boose available for the horses if we need it, though still I am dreaming of fields of tall green grass in Kafiristan.

At its highest section, the road precariously carves into the mountain side, leads through stone cliffs, rock completely overhanging the way. Virtually two miles of rock tunnel. I had been in this rocky tunnel two years before. Then I rode standing on the back bumper of a cargo jeep with two Pathan traders. We had to duck our heads in order to keep them from being chopped off by the sharp rocks overhead. The northern side of the road drops vertically straight off hundreds of feet down to the rushing Kalash River. High up on the opposite mountainside is what appears to be an even more precariously narrow road. In reality it is an aqueduct bringing water down to Ayun from higher up where the Kalash River comes out of Afghanistan.

The way is long and I speed up my pace. I want to arrive before the horses to make sure Habibullah has gotten it together. I don’t mind walking, in fact, I rather like it as long as I’m not carrying anything. Presently I’m only carrying my pistol and its weight bumps against my hip but it’s a feeling I’ve gotten used to. A nice reassuring feeling.

All the way into Kafiristan only two jeeps pass. One is full of tourists and they don’t stop to pick me up. I must look too Pakistani. The other is completely piled with Pakistanis. They really know how to load a jeep in these parts. Two fellows are perched on the hood and a double layer of passengers hang off the rear bumper. I shout to them as they grind dust and gears past me, asking if there is any room, but obviously there isn’t and they don’t bother breaking their momentum for me.

It takes me three and a half hours to cover the distance between Ayun and Bumburet. I walk past the Pakistani government check post at Dobash. I imagine I seem too local for them to bother with me. Even Pakistanis from other parts of Pakistan need to get a permit from the D.C. in Chitral to come here. The same happened the last time I passed this way, though at that time I was covered under the guise of a turban. Afghan Mujahideen don’t need any permit. I guess with my white Peshawari cap and pistol I look too Pathan to bother with. And everybody knows a Pathan’s pistol is his permit. What is the point of my entry permit?

I chuckle to myself thinking of a story told me by Anwar Khan in Peshawar about a policeman who asked a notorious badmash to show him his pistol permit. The badmash drew his pistol and shot the policeman in the leg. “Do you want to see another page now?” he asked the stunned policeman.

The first hotel to appear as I walk into Bumburet is the Benazir Hotel where I had stayed my last time in the valley. Thirsty, I don’t even mind paying eight rupees for a Shazan (four rupees at most in Peshawar). I know it is difficult to bring anything up here as it all has to come by jeep from Chitral. It’s hard enough getting anything up to Chitral. The Shazan is ice cold, having been submerged in a metal basket with other soft drink bottles in the cold stream across the road from the hotel. Dusk is falling as I trudge on up the road. I pass a few more small hotels. At one there is a familiar face sitting at a table under the veranda directly off the road.

I sit down with a Pathan in his early 30s from Tangi whom we had met on top of the Lowari Pass who had lived many years in England. He is just finishing filling a cigarette. A pot of chai arrives as I ask him if he has any news of Habibullah. As we are drinking the tea the chowkidar from the government rest house comes down the road looking for me.

In Chitral Mirza had obtained permission from the D.C. to stay at the guest house in Bumburet, but there is a slight problem. The guest house is under repairs. There is no electricity (the upper end of Bumburet Valley has electricity supplied by a small water-powered generator built by some Swiss people), no running water, no bathroom… nothing! He says Habibullah left all of our gear there but has gone down to the Kalash Hotel to see about making some other kind of arrangements.

As we talk we hear the sound of the horses’ bells like an audio mirage growing in the gloaming. A Kalashi boy comes running up the road heralding the approach of our little caravan. I see Mirza and Ayesha. The sun has just set. The air is calm, quiet, fresh. Nothing else is.

As they come up the road and into sight, sweat stained and worn out, the chowkidar is just finishing telling me the news of the guest house and of Habibullah. Just then Habibullah comes down the road. There is only one road running through Bumburet and the Kalash Hotel is further up the road, the guest house further still. After the guest house the rough dirt road becomes two trails, one leading south and up the mountain to the valley of Birir and the other following the Kalash River into Afghanistan.

We meet in confusion, all at once. Horse looks bad. Almost dead. He is covered in sweat, especially his head, neck and withers. His large eyes are closed and tears are staining his cheeks. Do horses cry? His legs are wobbling. He’s barely able to walk. I can see that Mirza and Ayesha are exhausted from the long day’s journey plus the mental and emotional strain of getting Horse this far. As we lead the horses up the road I explain to Mirza and Ayesha an English version of what the chowkidar has just completed telling me. At the same time Habibullah is telling me (in Pashtu, of course) what is happening with the Kalash Hotel.

He says there are two small rooms but he neglected to make any reservations because he was afraid to give them an advance on the rooms and find out we still wanted to camp out at the guest house. He still hasn’t quite to come to terms with the fact that even though we are Americans, and therefore “infinitely rich” and seemingly spending so much money on a horse trip of no apparent value, we still count and watch our every rupee, which I’m sure to him seems to be miserly fastidiousness.

“I know that hotel,” Mirza says. “I stayed there for a bit with my horse in 1983. There’s a huge grassy field right in front of it. A good place to tie the horses.”

“Noor Mohammada, selor Punjabian, samon sara, woose hotel la zee. Road banday ma ohleeda,” Habibullah informs me.

“Habibullah says that four Punjabis are on the road with packs, going toward the hotel now,” I tell the others.

Just then Horse collapses in the road. He won’t get up. Mirza, who has been leading him hands me his lead rope. I pull and Mirza whips his behind with his crop. “Get up you bloody bugger! Get up!” he screams.

“Quit it you guys!” Ayesha yells, “Can’t you see he can’t go on any more.”

Habibullah doesn’t say anything. He obviously can’t understand our actions and motives. He thought we should have taken the horses over the Lowari Pass in a truck. He just looked at me blankly when I explained to him that wasn’t the point of the trip and besides, after Chitral there would be mountains and passes much worse than the Lowari. If they couldn’t make it over the Lowari they’d never make it beyond Chitral.

“We’ve got to get him up,” Mirza shouts, “or he’ll die right here. He can’t spend the night here in the road. The hotel is less then a mile away. We’ve got to get him there.”

Finally Horse gets up and stumbles on.

“Noor Mohammada, zer makkhi lar shah. Haghwi Punjabian akhairi kambray ba akhlee, ou beir munga ba suh oku?” Habibullah tells me calmly in his low gravelly voice.

“Habibullah’s right,” I tell Mirza. “I’d better go ahead to the hotel quickly before those Punjabis get there and take the last two rooms. I’ll take Herc.”

I swing onto Hercules’ massive back and head up the road. Behind me I can still hear the other horses’ bells as our weary caravan struggles up the road in the rapidly darkening dusk. Hercules can sense the urgency of our flight and gallops up the road under me. We pass the four Punjabis and jump the small stream that crosses the path leading to the hotel.

The Kalash Hotel faces east, back down Bumburet Valley. The two-story, wooden building looks out over a large, semicircular grass field. The north side is bordered by the road, the south is ringed by a rock strewn ravine in which 30 feet below the Kalash River rushes noisily by. As I ride up to the hotel I can see some long haired tourists upstairs on the porch. I can smell the familiar sweet scent of charras in the air. Some Pakistanis and Kalashis standing around the front of the hotel watch in surprise as I gallop up. I dismount and quickly tie Hercules to one of the poles holding up the porch.

A short man approaches me followed by two others. He’s wearing a Nuristani (pakul) cap over his greasy black hair that hangs down behind his ears grimy with dirt. His pocked complexion also has an unwashed pallor and he looks at me through close-set, small, piercing black eyes.

Abdul Khaliq is the proprietor of the Kalash Hotel. I explain our situation to him. By the time we hear the horse bells approaching the hotel hasty preparations have been made. Several fellows go off to cut and fetch fresh, green cornstalks for the horses’ dinner. The sound of the bells waxes louder and our footsore little caravan appears in the approaching night.

“What’s happening, Noor?” Mirza asks me wearily.

“Look, come, we’ll unload the horses here in front of the hotel. Then we can stake them over there.” I point with my hand in the darkness to the edge of the field bordering the river ravine. “I’ve already arranged for some men to bring down fresh green cornstalks from the fields.”

As we talk I am still finalizing arrangements with the hotel’s jeep driver to drive Habibullah up to the guest house to get the rest of our gear. We leave the other three horses tied to the porch supports and take Horse down to the field under a tree. He collapses and is breathing very hard, lying flat on the short turf. After a time he lifts his head and then rises to urinate. Mirza walks him around. His abdomen is completely swollen. He alternately lies, rolls and gets up on wobbly legs. When he rises Mirza walks him gently until he falls again. We cover him with our blankets.

Ayesha and I unload the other horses in the light of the bare light bulbs hanging on the porch. Habibullah I send off in the jeep to collect our gear. We need the moogays to stake the horses securely for the night, plus we want the animal tranquilizers for Horse.

At a quarter to midnight I’m squatting outside the cookhouse talking and smoking with the cook. He’s an Afghan from up the valley in Nuristan. Ayesha and Habibullah are asleep in their respective rooms. Mirza is lying in the field next to Horse, propped up by his saddle and covered with a blanket. I hear him call out to me. I go down and join him next to Horse.

“Horse just had some really bad convulsions,” he says.

“Do you think he’ll make it?” I ask.

“I don’t know Noor. God, I wish now that I knew more about horse medicine. This is all my fault for not knowing more. I brought Horse into this and I don’t know enough to get him out.”

“It’s nobody’s fault. These things happen. It is the way God wills it.”

Horse gets up and we gently lead him as he walks himself. Then he starts to topple again. He’s falling against Herc and Herc can’t get away because he’s at the end of the rope he is staked to.

“Pull him Noor!” Mirza says hurriedly, pushing him with his shoulder to try to keep him from crashing against Herc. Mirza pulls out the razor sharp knife he wears on a sheath around his neck and with one quick sweep slices through the thick rope, freeing Hercules. Horse hits the grass. He’s lying on his side and kicking violently. The cook comes down and squats beside us.

“You should cut a hole in his stomach to let the air out,” he tells me in Pashtu. I translate this grisly information to Mirza.

“I’ve never heard of that,” he tells me. “I’m afraid it will kill him. I still think he can make it if he can just make it through the night.”

Horse stops kicking and holds his head back stiffly. Low, raspy breaths come from deep down in his throat. It’s his death rattle.

“Cut his throat now,” the cook tells me. “Halal him, and then at least the Muslim people up the hill can eat him.”

I tell Mirza what the cook has said but he can’t hear. We both feel that some miracle will pull him through and he’ll be recovering in the morning. But it is not to be. It’s too late. He’s dead.

HE’S DEAD

“He’s dead,” Mirza said in English.

“He’s dead,” the cook and I echoed in Pashtu.

“I can’t believe he’s dead,” Mirza said, dazed.

“You should have halaled him,” the cook went on, “then the Muslim people could have eaten him. Well, no matter, it’s not a waste. The Kafir people don’t care about halal, the eaters of filth. They will eat him anyway.”

That I didn’t bother to translate.

We covered Horse with our plastic tarp and a rain poncho. A beautiful, silvery full moon was rising over the mountains heralded by a pearly glow rimming the hill tops. A few silver-lined clouds highlighted the star-studded sky. The moon and starlight reflected diamonds in the ripples of the stream as it splashed over white stones below us down the moss-covered rock-strewn river banks. Horse’s body was laying on the greensward, half-a-ton of lifeless, stiffening meat. Life had fled him as the sun had fled the day’s sky. The night was still, quiet and peaceful. It was seven minutes after midnight. Mirza and I watched the silent moon rising, neither speaking….

After a time we went upstairs and quietly entered Ayesha’s room. She was asleep, exhausted on a charpoy, still in her travel-stained clothing. On the other charpoy our equipment was piled. On top our rifles and Ayesha’s pistol and turban lay perched. At first she couldn’t believe, or wouldn’t comprehend, that Horse had died. Then she began to softly weep.

I left them alone in the room with their sadness shared and sat at the table on the porch alone in the night and filled a cigarette. As I smoked I looked down on the moonlight bathed field. Over by the tree near the edge of the ravine was the covered lump that had been Horse. Wrapped in my blanket, I gazed at the crystal bright moon in the sky, shivered and thought of sitting on a charpoy cozily with Nasreen on a warm night in Lahore (sweating).

Mirza and Ayesha emerged from the room and we went down to the field so she could see Horse. She petted his soft, cold nose. Only the wind in the leaves and the crickets spoke in the velvet mountain night. The three of us went back to the porch and sat silently at the table until 3:00 A.M., each in our own private thoughts. I went to my room, an eight by eight cubical with the floor covered with colorful quilts, to get a bit of sleep. No need to wake Habibullah I reasoned. He could wait until morning for the bad news.

At 5:30 I awoke and went outside. Horse was still laying there, an olive green covered mass on the emerald dewdrop sparkling grass.

His body was completely bloated. Last night had really happened. I hadn’t dreamt it.

The other horses were standing oblivious in the quiet morning air. Mirza and I had moved them in the night to the other side of the field. They didn’t seem to notice their dead companion as they calmly munched corn stalks. As I stood quietly looking at the pile of cold stiffening meat that was our traveling companion the hotel owner, Abdul Khaliq, came and stood beside me.

“So sorry about your horse,” he said shallowly.

“Yeah, so are we,” I said, already taking a dislike to the shifty little man. “God knows better.”

“What do you want to do?” he started in. “We can’t leave him here. It’s not good for the hotel. And the local people are superstitious about such things. Yes, we must do something about him right away.”

Already some local children were gathering around looking.

“We can get some men and a jeep to haul him away and bury him in the mountains,” Abdul Khaliq continued.

“What’s going on Noor?” Mirza asked as he joined us sleepily by Horse’s side, his blue turban wrapped haphazardly around his head.

“Well, Abdul Khaliq here says he can get a jeep and some men to haul Horse away and bury him in the mountains,” I informed him. “We can’t leave him here.”

“Yeah, we must bury him,” he agreed. Turning to Abdul Khaliq he asked, “How much will it cost?”

Abdul Khaliq thought for a moment. He squinted and scanned us with his crafty eyes. “The jeep will be 1000 rupees. And then we must give the men each something for their work.”

“You can’t get a jeep for less then that?” I asked. It seemed rather dear.

“I don’t think so, my brothers. We can’t bury him near here. He will have to be taken a long way up into the hills.”

“God’s blood, it does seem expensive,” Mirza said. “But he was our mate. We brought him all the way here to die. We have to bury him.”

By now Habibullah and Ayesha had joined our grim little circle and I explained what was happening to Habibullah in Pashtu while Mirza explained to Ayesha in English. Abdul Khaliq stood by and looked at Horse, grinning. Ayesha agreed that the expensive price no matter, Horse must be buried at all costs, what else was there to do? After the events of the previous day we were all in a state of slightly shocked stupor to say the least. Habibullah just stood there silently as I told him. He understood enough to know that, as it wasn’t his money what he thought was of no real consequence anyway.

“Okay. I will go see about arranging the jeep,” Abdul Khaliq said as he walked off still grinning.

“Hagha mor ghod Kafir, ohgura. War-rawan day po ohkhanday, dah da hagha mor kus ohghaim. Sta po makh banday ghool okama, banchoda!” Habibullah said under his breath.

“What was that, Habibullah?” Ayesha asked.

“Oh, he said,” I took the liberty of answering for him, “Look at that no good Kafir. He’s smiling as he walks away!”

“Are you sure that’s all he said, Noor Mohammad?” she asked, having picked up quite a smattering of Pashtu herself. “I thought I heard some other words I recognized. I think I heard some of them when you were speaking with the truck drivers.” she teased.

“Ayesha, my dear, do you doubt my linguistic abilities? Sister, I speak truth! Now let’s go back to the hotel and have some breakfast.”

We sat at the table on the porch outside our rooms and ate in silence a breakfast of chai, greasy parattas and greasier fried eggs. None of us could think any further into the trip than the present: what should be done with the lifeless carcass of Horse and what to do with the three remaining horses that morning? As we ate, Abdul Khaliq came up on the porch and stood by the table. “I can’t arrange a jeep,” he started in suspiciously.

“What do you mean?” Mirza jumped in. “We have to do something about our horse.”

“Yes, for sure, brother. But my jeep is gone and there isn’t another available just now.” He hesitated briefly and with a badly hidden grin on his face he continued, “Look, my friends, here is the only solution for you. We need to do something quickly, yes? I can get some men who can cut him into pieces. Then they can carry the pieces up to the mountains in baskets and bury him. It’s the only way I can arrange.”

Ayesha naturally freaked at the idea of cutting up Horse. Mirza and I looked at each other in bewilderment. Habibullah sat and went on drinking his tea as we were talking in English and he hadn’t understood a word of what was going on.

“Look, Abdul Khaliq,” Mirza said, “let us discuss this among ourselves. Then we will tell you.”

“Okay, talk friends, but decide. We must do something quickly,” he said, leaving us alone on the porch.

As we were all in an emotional and physical state of shock we decided there wasn’t really anything else we could do. We were stuck in Kafiristan and our horse lay dead on Abdul Khaliq’s lawn. The greedy Kafir, Abdul Khaliq, played on the emotional attachment he knew Westerners have for animals. Had we been Pathan we would have just said, “So what, he’s dead in your field, Kafir. It’s your problem now.”

We decided Habibullah and Ayesha would take the horses across the road and up the hill to a rock wall corral to bathe them. Lord knows they needed it; they hadn’t had a good washing since down country—and we didn’t want them to witness what was going to happen to their dead companion, Horse, though in afterthought I think it was more to satisfy us than any of the horses’ needs. For sure we didn’t want Ayesha there to witness the macabre scene that would be unfolding in Abdul Khaliq’s field.

Five men arrived with baskets, axes and large butcher knives. They wanted to chop him up down by the river where there was water available, plus out of sight of the inhabitants of the hotel. Too heavy for them alone, Mirza, Habibullah, Abdul Khaliq and I helped drag his stiff, lifeless form to the edge of the ravine. We rolled him over the edge and his big, bloated body rolled and crashed down on the rocks of the river bank below. We heard the sickening crunch of the bones in his legs snapping. Just a heavy, cold piece of spoiling meat now, though just yesterday he had been Horse. Well, that’s life… and death. One day we all become just dead meat, don’t we?

They took out their knives to skin him. They were only visible if you stood on the side of the ravine and looked down but the thudding blows of their axes could be heard in the hotel, the cold thuds of butchers chopping through meat, gristle and bone. Mirza and I walked down the road to look for grass to buy to feed the remaining horses. Or maybe a field of green grass to rent? Before we left I walked over to the edge of the ravine to see the butchers’ progress. Just as I arrived at the edge they were chopping off Horse’s head. Big, beautiful Horse, his large, sweet eyes. Now just meat. Rather grotesque but we are so far away from the world we had come from.

As we walked down the road a ‘hippyish’ looking moustached fellow with longish hair approached us. He was a Pakistani artist from Lahore. We introduced ourselves and had a bit of a chat. Even though Mohammad Bugi is a Muslim, from Lahore, he has been working wholeheartedly on preserving the Kalash arts and culture. He was in the process of putting on the first art workshop and show in the long history of Kalash. He had seen us riding in yesterday. He told us of the Frontier Hotel just down the road. It was run by a Muslim and there was room for us. We wanted to get away from the Kalash Hotel and its Kafir owner Abdul Khaliq. We wanted to forget what had happened there.

When we went back to the Kalash Hotel to fetch our little caravan Horse’s white skin was laying stretched out on the ground next to the rivulet by the path leading to the hotel (not a good omen).

Now I’m sitting on the porch of the Frontier Hotel. The horses are with Habibullah grazing in a field of grass behind the hotel. The field isn’t completely horizontal but it should keep the horses in green grass for at least a week. The hotel proprietor, Shukar Ali, helped us negotiate with a Kafir farmer, Ditullah Khan. It was confusing, the languages flying, but accomplished in the end. Ditullah Khan talking to Shukar Ali in Kalashi, Mirza talking to me in English and Shukar Ali and I bringing it together in Pashtu.

Ditullah Khan and his wife are Kafir. Kafir men wear the same clothes as Muslim men; usually shalwar kameez, waistcoat and woolen pakul caps, though their women dress differently than their Muslim sisters. They wear black, coarse cotton, ankle-length dresses with red, orange and yellow embroidery and caps with similarly-styled embroidery plus a mixture of red and bright phosphorescent colored plastic beads, cowrie shells and coins. They never go veiled. They also wear a profusion of red bead and cowrie shelled necklaces. Many make a paste of burnt goat horn (called Puru) and decorate their faces with black dots and patterns. It appears to be made from mud.

Ditullah Khan’s daughter, about 17, also confuses me. She dresses in Muslim clothing but Shukar Ali tells me it isn’t unusual in Kafiristan for individual family members to become Muslim, thus making Kafirs and Muslims in the same family. Also some girls choose to become Muslim in order to avoid the obnoxious attentions of Pakistani men tourists, who credit the Kafir women with a very loose reputation (though I find many Pakistani men think that about any woman who is not veiled or in the house).

As I sit here and write, Ditullah Khan’s daughter is sitting on the hillside opposite the porch watching me. She smiles coyly every time I look her way. Is she just curious and friendly or is she making eyes at me? Are the Pakistani stories true or have I just become too Pakistani to be able to rightly judge anymore?

PIXEL – A REVOLUTION IN ART

DHA, Lahore Cantonment, Pakistan-54000

Phase III Behind Chenone, DHA, Lahore, Pakistan

is attending a Group show

after absence of 21 long years

He is settled in Holland

where he does FREE ART Work Shops

to Promote Pakistani Culture

KAFIRISTAN

June 20th

‘Rest day’ in Drosh.

Misra and Habibullah go to Chitral to talk to the D.C., to get permission to enter Kalash, and to check on horse food. Ayesha and I spend hours looking for food for the horses in Drosh. We walk though the fields trying to find some wheat that has been threshed so we can get some boose (straw). Combing the bazaars for flour, barley, anything. Never thought we’d be so happy as to find a sack of barley. The flies in the barren lot behind the hotel the boys are staked out in are loathsome. The stench of their old bread and barley shit is nauseating.

The next morning we leave Drosh. Horse’s withers are bad, and coming down the Lowry Pass Shokot’s withers have started developing the same type of hard lump that Horse started with.

Misra rides Hercules and Ayesha rides Kodak. Habibullah and I walk leading Horse and Shokot. We stop at an animal husbandry hospital on the outskirts of Drosh to see what can be done for them. The dispenser washes their wounds with the same orange wash we are using. Then he powders them with the white powder. He has a boy bring out a bottle of oxi-tetracycline. There is only one shot left in the bottle, the rubber seal has already been punctured, and he plunges the dark green fluid into Horse’s neck.

The boy goes to the bazaar to bring some more. We have tea with the dispenser on the veranda. The liquid in the fresh bottle is a pale amber color. He gives Shokot a shot. Misra and Ayesha leave Drosh ponying Horse and Shokot. Habibullah and I remain to get supplies and hire a jeep to Ayun. It’s enjoyable doing business in the bazaar with Habibullah. Habibullah does the bulk of the talking. No one knows I’m foreign. Just a couple of simple Pathans from down country. It’s nice not being the show for a change, just a part of it.

Habibullah and I hire a jeep to take us and the gear to Ayun. Habib will find another jeep there, insh’Allah to take him on to Kafiristan. I plan to meet Misra and Ayesha at the old suspension bridge spanning the river. We pass them on the road. An hour later I get off before where the bridge, built in 1927, crosses the muddy rushing Chitral River. Beyond the bridge the road becomes dusty dirt, on the west bank of the river, on to Ayun. It saves the distance of first riding to Chitral before back tracking to Ayun. Misra has already obtained our passes to enter Kafiristan when he had gone to Chitral with Habibullah. My job is to wait at the bridge for them to help them cross the four horses over.

I sit on a grassy hill side overlooking the river with streamlets of clear cool water gurgling through the short grass and tumbling down the rocky banks to join the swirling river. I smoke a cigarette and idly watch some grazing sheep.

Misra, Ayesha, and the horses arrive shortly after noon. Before crossing they join me on the grass for lunch. A can of sardines, crackers and water. Asadullah wants to take pictures documenting our crossing of the suspension bridge but it is not to be. Before we can shoot anything a soldier comes up to us and tells us that it is illegal to photograph the bridge. He is an older soldier, approaching middle age and a potbelly, who could probably only be posted in such a useless post as guarding some stupid bridge (in all fairness we were right on the war sensitive Afghanistan border).

We show him our letters from Islamabad, first the English one to duly impress, then the Urdu one so he can read it. He’s rude. He can’t read Urdu very well anyway.

“We don’t give a shit about your stupid bridge, anyway.” I tell him. “We just want pictures of our horses crossing it. What importance can it have? It’s an antique. That is why we want the pictures.”

Misra and I discuss shooting him, but wisely decide just to head on. We still have a long hot ride to Kafiristan, and besides, bullets are costly.

After crossing the bridge I walk along with them leading Horse. He is becoming lethargic and needs to be coaxed along. The bank of the river is rocky and forty feet below us. The water is impossible to get to. In half an hour I decide to try to catch a ride on the next jeep passing us, to get into the valley of Kafiristan before the horses and to make sure all arrangements are satisfactory.

Kafiristan is the home of the Kafir Kalash – primitive pagan tribes, known as the wearers of the black robes. Their origin is cloaked in controversy. Legend says that five soldiers from the legions of Alexander the Great settled there and are the progenitors of the Kalash. They live in three valleys in small villages built on the hill sides near the banks of the Kalash River, and it’s tiny tributaries, in houses of rough hewn logs, doubled storied because of the steepness of the slopes. The lower portions are usually for animals and fodder storage for the long harsh winters. They practice a religion of worship of nature. It is the only area in Pakistan-Afghanistan that hasn’t been converted to Islam, though that is slowly changing with the times. Across the mountains, in Afghanistan, the Kalash were converted in the 1890’s by Amir Abdur Rahman, the iron amir of Kabul, and Kafiristan became Nuristan.

Fifteen minutes after walking on ahead of Misra and Ayesha a jeep passes. I climb in. On the front seat are two fellows along with the driver. The older of the two, with a bushy brown wavy beard and wearing a pakul cap, asks me if I have heard of Rambur Valley. He tells me he is the headman of the village of Rambur. I vaguely remember him but to my good luck he doesn’t recognize me. When he last saw me, two years ago, I was speaking Farsi and English, not Pashtu. We had fought because I had defecated down by the river, which I hadn’t known at the time, was their Kafir holy place. He had wanted me to wash in the river to rectify it but I wasn’t going to bathe in that icy cold water. I told him the hell with him and his foolish Kafir superstitions. I promptly left and walked the ten miles back to Bumburet.

We drive past the Kafiristan turnoff, a steep dirt road leading up and west, leading into the narrow valley of Kafiristan. The jeep stops short of Ayun and I walk the remaining distance. Habibullah isn’t anywhere to be seen. I assume he has gotten a jeep into Kafiristan and that everything will be prepared for our arrival.

I sit at a table set up in the wide dusty street with some chairs around it and a tattered canvas overhang overhead to shield customers from the sun and drink a mango sherbat with delightfully cold dirty shredded snow ice. Ayun is dead, as usual. It always reminds me of a semi-deserted western ghost town. It is getting late in the day, almost 3 P.M., and there aren’t even any jeeps waiting around to go to Kafiristan. I decide to start walking the distance. I can’t sit and if a jeep does come through there is only one road. And I’ll be on it.