http://www.indigenouspeople.net/kwakiut.htm

Kwakiutl Literature

NOTES FROM “THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN”

See page for gravures of Curtis’ work.

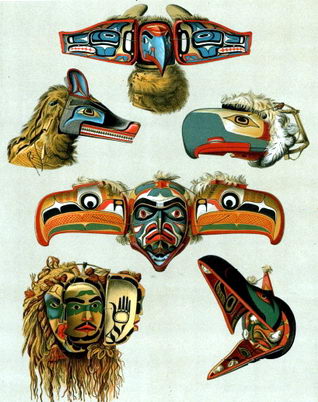

QUOTES:: “Of all these coast-dwellers the Kwakiutl tribes were one of the most important groups, and, at the present time, theirs are the only villages where primitive life can still be observed. Their ceremonies are developed to the point which fully justifies the term dramatic. They are rich in mythology and tradition. Their sea-going canoes possess the most beautiful lines, and few tribes have built canoes approaching theirs in size. Their houses are large, and skillfully constructed. Their heraldic columns evidence considerable skill in carving…. In their development of ceremonial masks and costumes they are far in advance of any other group of North American Indian.”

“Of medium stature, the Kwakiutl are as a rule well formed and strongly built. The face is very characteristic, being usually high and with a prominent, frequently hooked, nose not found among other North Pacific tribes. Head-flattening was an invariable practice, and most of the elderly people have artificially lengthened heads…Until about the middle of the nineteenth century artificial deforming of the head was general among the Kwakiutl, while the tribes along Quatsino sound carried the practice to greater extremes….A pad of floss was bound tightly over the forehead, and other pads were stuffed into the space between the temples and the sides of the cradle, the purpose being to produce a straight line from the tip of the nose to the crown of the head. It was regarded as little less than disgraceful for any one, especially a woman, to have a depression where nose meets forehead.”

“Of all the art and industries practiced by the Kwakiutl tribes none reached a higher development than the art of working in wood. The principal phase of this work – the riving of cedar planks – has become obsolete because the necessity that mothered the art no longer exists; but splendid canoes, serviceable, water-tight chests, ponderous feasting dishes, ingenious masks, and a host of indispensable utensils are daily manufactured with the most elementary tools.”

“In preparation for curing, the fish is opened at one side of the backbone, which is then removed with the head and laid aside. The roe is thrown into another heap, the entrails and gills are rejected, and the flesh, inside and outside , is rubbed off with a handful of green leaves. The strip along each side of the back is cut off and sliced into a thin sheet, leaving the fish itself of uniform thickness of the flesh at the belly. Held open by skewers, this is hung up to dry, first in the sun, then in the smoke of the house-fire. The thin sheets are hung on poles to become partially dry in the sun; and then skewers are inserted to prevent curling as they thoroughly dry out in the smoke. Above the fire are five tiers of racks, and each lot of salmon spends a day on each of the first four, beginning on the lowest. After five days on the topmost tier the cured flesh is packed in large bag-like baskets or in cedar chests, which are kept in a dry place.”

“Those who have to do with the curing of sickness fall into four classes. One who by ‘eka’ (sorcery effected by sympathetic magic) encompasses the illness and finally the death of an enemy is called ‘ekenoh,’ that is, one skilled in sorcery. Such a one also has the power to counteract the evil works of his colleagues. The medicine-man, or shaman, expels or induces occult sickness by the direct exertion of his preternatural power upon the body of the patient or the victim… Those who by the operation of sympathetic magic but without any alleged direct connection with supernatural beings, obtain good results in healing are ‘pepespatenuh.’ The healer who treats understood ailments and employs no means other than vegetal or animal remedies is called ‘patenuh’ or medicine givers.”

Legends

We have been called the Kwakiutl ever since 1849, when the white people came to stay in our territories. It was a term then applied to all the Kwakwaka’wakw—that is, all of the people who speak the language Kwakwala. Today, the name Kwakiutl only refers to those from our village of Fort Rupert. Other Kwakwaka’wakw have their own names and villages. For example, the Gwawa’enuxw live at Hopetown. Collectively, we call ourselves the Kwakwaka’wakw—that is, all of the people who speak the language Kwakwala.

Archaeological evidence indicates that our people have occupied Vancouver Island, the adjacent mainland, and the islands between for about nine thousand years. Before the Canadian government contracted our traditional boundaries to enclose small reserves, each tribal group owned its territory, through which it moved seasonally. During the winter, each occupied a more permanent site, where the people engaged in intensive ceremonial activities while enjoying the abundant supply of foods from the sea and land that they had gathered earlier in the year.

With the introduction of European technology and food, much of the traditional subsistence cycle was altered. A variety of salmon and shellfish are still gathered and preserved by freezing, canning, or smoking, and the spring runs of eulachon (candlefish) in Knight and Kingcome Inlets are still harvested and rendered into oil.

According to Mungo Martin, the Kwakiutl lived at Kalugwis before 1849, when the Hudson’s Bay company built a fort at Fort Rupert. When they moved to Fort Rupert the village site was at times occupied by the Lawit’sis. The Kwakiutl proper were descended from an old Kwakiutl tribe that split because of a dispute. A warrior named Yakodlas murdered Chief ‘Makwala (or T’tak’wagila) and his faction became the Kwaixa or “murderers”, the others became known as the Kwixamut, “fellows of the Kwixa” but they kept the Kwakiutl name. Both factions also took on other names to glorify their status. The Kwakiutl were the Gweetala or “northern people” and the Kwixa were K’umuyoyi or “the rich ones”.

Before the middle of the 19th century, the present area of Fort Rupert village had very little permanent settlement, but was the site of an enormous bank of clamshells, two miles long, half a mile wide and fifty feet high. The shells were the last vestiges of enormous feasts held here for generations and they came to play a part in local history in World War II when they were used to level the nearby Port Hardy airport.

Other visible aspects of Fort Rupert’s cultural fabric include a historical graveyard, the old chimney which marks the site of a former Hudson’s Bay Company fort and an impressive Big House.

Petroglyphs, one of which dates back to 1864, are not easy to find, but they do exist on sandstone formations in the upper tidal in front of the old fort site.

Our Language

Our Kwakiutl language or Kwak’wala is a Wakashan language of the Northwest Coast, traditionally spoken in our territory. Kwak’wala is the term used for the language, and Kwakwaka’wakw for the ethnic group. The Kwakwaka’wakw, or Kwak’wala speakers are the original inhabitants of the Northern Vancouver Island area. A region in mainland British Columbia was also occupied by them. The ethnic population is now 5.517 (1996) but there are only some 200 Kwak’wala speakers which account for less than 4% of the Kwakwaka’wakw population. While the language has been in decline, we are working hard to keep our ancestral language alive.

The term “Kwakwaka’wakw” was only recently coined, because there is no historic name or even a strong sense of Kwakwaka’wakw identity, though the people are joined by language, culture, and economy.

At the time of European contact in 1786, the Kwakwaka’wakw formed between 23 and 27 tribes or family groups, each allied to one chief. There was always intermarriage between groups and considerable movement for economic reasons. For example, if the chief of one group acquired a reputation for giving lavish potlatches, his group would likely increase. Each group had its own places to dig clams, fish, and so forth. Originally they were restricted nomads, moving from winter clamming beds, to spring eulichan (smelt) runs up the rivers, to summer fishing grounds. Sometimes two or more tribes shared the same village site, and group boundaries were constantly shifting owing to splits, mergers, and wars.

The coming of Europeans sped up the pace of change. Conflicts became bloodier with the introduction of guns, and new diseases decimated the population. The estimated pre-contact Kwakwaka’wakw population of 19,125 fell to just 1,039 in 1924 (Galois, 1994). Change accelerated in 1849 when the Hudson Bay Company built Fort Rupert. All the tribes came here to trade, and conflicts increased with more contact.

The lack of strong Kwakwaka’wakw identity has hindered efforts to revive the language. There is little interest in learning a dialect different from one’s own, and there are five dialects. Fort Rupert was built on the Kwakiutl land, and the famous anthropologist Franz Boas further increased the prestige of the Kwakiutl through his lifelong study of them at the end of the nineteenth century, resulting in two shelves of ethnographic and linguistic materials. For these reasons, the terms Kwagiulth or Kwakiutl and the concomitant Kwak’wala became the general term for all 12 surviving groups.

The most commonly expressed reason for the decline of Kwak’wala by the Kwakwaka’wakw is that they were forbidden to speak it at St. Michael’s Residential School in Alert Bay, which operated from the 1920s to the 1970s. Most Kwakwaka’wakw children, as well as children from non-Kwak’wala speaking villages to the north, attended and boarded at St. Michael’s. Further study shows other reasons for the decline. Kwak’wala usage declined in lockstep with the Kwakwaka’wakw culture. Kwak’wala speakers are being attacked on many fronts. The Kwakwaka’wakw have been colonized and marginalized, and their language suffered in prestige by its association with their disadvantaged culture.

Rebirth

Although the emphasis for the Kwakwaka’wakw is primarily on spoken Kwak’wala, it is also desirable for all Kwakwaka’wakw to be able to read and write the language as well. In particular, it is important that adult Kwak’wala literacy go hand in hand with school programs providing Kwak’wala literacy for children. (see the description and Contact info for the Wagalus School on the Member Services page) In this way, the generations can be united through Kwak’wala literacy, rather than separated. Adult and child literacy can be a good way to strengthen the crucial intergenerational link. In order for adult literacy to take place, we will work toward easy-reading literacy materials and a dictionary.

Potlatch

Throughout native North America, gift giving is a central feature of social life. In the Pacific Northwest of the United States and British Columbia in Canada, this tradition is known as the potlatch. Within the tribal groups of these areas, individuals hosting a potlatch give away most, if not all, of their wealth and material goods to show goodwill to the rest of the tribal members and to maintain their social status. Tribes that traditionally practice the potlatch include the Haidas, Kwakiutls, Makahs, Nootkas, Tlingits, and Tsimshians. Gifts often included blankets, pelts, furs, weapons, and slaves during the nineteenth century, and jewelry, money, and appliances in the twentieth.

The potlatch was central to the maintenance of tribal hierarchy, even as it allowed a certain social fluidity for individuals who could amass enough material wealth to take part in the ritual. The potlatch probably originated in marriage gift exchanges, inheritance rites, and death rituals and grew into a system of redistribution that maintained social harmony within and between tribes.

When Canadian law prohibited the potlatch in 1884, tribes in British Columbia lost a central and unifying ceremony. Their despair was mirrored by the tribes of the Pacific Northwest when the U.S. government outlawed the potlatch in the early part of the twentieth century. With the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 in the United States and the Canadian Indian Act of 1951, the potlatch was resumed legally. It remains a central feature of Pacific Northwest Indian life today.

Purpose

A ranking Kwakiutl was concerned that others should recognize his claims and status. This concern was expressed in the potlatch, which provided a channel for claims of status to be made publicly, privileges to be displayed, and ceremonial hospitality to be offered. By accepting suitable gifts, guests in effect received payment as witnesses. The claims thus established by the host would be accepted at future potlatches.

Procedure

The basic procedure of the potlatch was always the same. The lineage chief would consult with the older members of his household group, for the potlatch involved the entire household or kin group. When it was agreed that a potlatch should be held, a date was set, and preparations began.

Enough food to feed the expected guests was gathered, prepared and stored. Gifts for all were produced, and the needed goods bearing the family crest were amassed. The carver of the chief often lived in the chief’s household, and since he knew all of the inheritances he cold carve any item with appropriate designs.

Often loans had to be called in in order to make enough gifts available. A system of loans and interest was an elaborate aspect of Kwakiutl life. Most public actions were financed by loans of white wool blankets, valued at one dollar each, which had been brought in by the Hudson’s Bay Company early in the nineteenth century.

Emissaries of the chief set off to invite the guests, and when it came time for the event, these same emissaries, wearing formal costumes, went back to act as guides for the visitors. The family of the host with the song leader and speaker, in their finest robes and headdresses, stood upon the beach singing and dancing to greet the visitors as they approached by canoe.

Since the potlatch was tied in with many social occasions great and small, it varied in length. Food dishes were brought in, as the herald explained the ancestral names of the dishes and their history. One or more major events would be offered as a feature of each day. Family dances and dramas were enacted, and sometimes members of the family were initiated into dancing societies.

If the potlatch was successful, all of the family shared in the glory and pleasure of the social effort.

The Kwakwaka’wakw peoples are traditional inhabitants of the coastal areas of northeastern Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia. In the 2016 census, 3,670 people self-identified as having Kwakwaka’wakw ancestry.

Population and Territory

The Kwakwaka’wakw peoples are traditional inhabitants of the coastal areas of northeastern Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia. In the 2016 census, 3,670 people self-identified as having Kwakwaka’wakw ancestry.

Originally made up of about 28 communities speaking dialects of Kwak’wala — the Kwakwaka’wakw language — some groups died out or joined others, cutting the number of communities approximately in half. After sustained contact beginning in the late 18th century, Europeans applied the name of one band, the Kwakiutl, to the whole group, a tradition that persists. The name Kwakwaka’wakw means those who speak Kwak’wala, which itself includes five dialects. (See also Northwest Coast Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Pre-contact Life

Archaeological evidence shows habitation in the Kwak’wala-speaking area for at least 8,000 years. Before contact with Europeans, Kwakwaka’wakw fished, hunted and gathered according to the seasons, securing an abundance of preservable food. Consequently, this allowed them to return to their winter villages for several months of intensive ceremonial and artistic activity. In addition, trails across Vancouver Island made trade possible with Nuu-chah-nulth villages on the west coast of the island.

The culture of the Kwakwaka’wakw is similar to that of their northern neighbours, the Heiltsuk and Oowekyala peoples. The potlatch, for example, is a ceremony that the Kwakwaka’wakw and some other Indigenous nations in British Columbia have been hosting since well before European contact. Though it was once outlawed by the Indian Act, the potlatch remains an important part of modern community life.

The Kwakwaka’wakw are known for their artwork, distinct from other Northwest Coast Indigenous art in its style and cultural significance. In the carving of totem poles, for example, the Kwakwaka’wakw are known to carve creatures with narrow eyes, whereas the Haida poles typically have bold eyes.

Language

A member of the Wakashan language family, Kwak’wala is related to other Indigenous languages in British Columbia, such as those of the Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka), Heiltsuk (Bella Bella), Oowekyala and Haisla (Kitamaat). The Kwak’wala language is considered endangered;today, most Kwakwaka’wakw children speak English as their first language and there are few fluent speakers. In 2016, Statistics Canada reported 585 Kwak’wala speakers (though this figure does not specify their fluency level), with the majority living in British Columbia (98.3 per cent). As a means of preserving the language, some schools in the area sponsor programs in Kwak’wala.

Kwakiutl Band Administration

99 Tsakis Way, Fort Rupert

PO Box 1440

Port Hardy, BC V0N 2P0

Phone: 250-949-6012

Fax: 250-949-6066

reception@kwakiutl.bc.ca

I coud noot refrain from commenting. Veryy wsll written!

LikeLike