Acoma/Laguna Pueblo Literature

Stories

Blue Corn Maiden and the Coming of Winter

How the Turtle out hunting duped the Coyote

Origin of Summer and Winter (Acoma/Laguna)

Origin of Summer and Winter (ver. 1)

Origin of Summer and Winter (ver. 2)

Origin of Summer and Winter (ver. 3)

The Acoma chief had a daughter named Co-chin-ne-na-ko, called Co- chin for short, who was the wife of Shakok, the Spirit of Winter. After he came to live with the Acomas, the seasons grew colder and colder. Snow and ice stayed longer each year. Corn no longer matured. The people soon had to live on cactus leaves and other wild plants.

One day Co-chin went out to gather cactus leaves and burn off the thorns so she could carry them home for food. She was eating a singed leaf when she saw a young man coming toward her. He wore a yellow shirt woven of corn silk, a belt, and a tall pointed hat; green leggings made of green moss that grows near springs and ponds; and moccasins beautifully embroidered with flowers and butterflies.

In his hand he carried an ear of green corn with which he saluted her. She returned the salute with her cactus leaf. He asked, “What are you eating?” She told him, “Our people are starving because no corn will grow, and we are compelled to live on these cactus leaves.”

“Here, eat this ear of corn, and I will go bring you an armful for you to take home with you,” said the young man. He left and quickly disappeared from sight, going south. In a very short time, however, he returned, bringing a large bundle of green corn that he laid at her feet.

“Where did you find so much corn?” Co-chin asked.

“I brought it from my home far to the south,” he replied. “There the corn grows abundantly and flowers bloom all year.”

“Oh, how I would like to see your lovely country. Will you take me with you to your home?” she asked.

“Your husband, Shakok, the Spirit of Winter, would be angry if I should take you away,” he said.

“But I do not love him, he is so cold. Ever since he came to our village, no corn has grown, no flowers have bloomed. The people are compelled to live on these prickly pear leaves,” she said.

“Well,” he said. “Take this bundle of corn with you and do not throw away the husks outside of your door. Then come tomorrow and I will bring you more. I will meet you here.” He said good-bye and left for his home in the south.

Co-chin started home with the bundle of corn and met her sisters, who had come out to look for her. They were very surprised to see the corn instead of cactus leaves. Co-chin told them how the young man had brought her the corn from his home in the south. They helped her carry it home.

When they arrived, their father and mother were wonderfully surprised with the corn. Co-chin minutely described in detail the young man and where he was from. She would go back the next day to get more corn from him, as he asked her to meet him there, and he would accompany her home.

“It is Miochin,” said her father. “It is Miochin,” said her mother. “Bring him home with you.”

The next day, Co-chin-ne-na-ko went to the place and met Miochin, for he really was Miochin, the Spirit of Summer. He was waiting for her and had brought big bundles of corn.

Between them they carried the corn to the Acoma village. There was enough to feed all of the people. Miochin was welcome at the home of the Chief. In the evening, as was his custom, Shakok, the Spirit of Winter and Co-chin’s husband, returned from the north. All day he had been playing with the north wind, snow, sleet, and hail.

Upon reaching the Acoma village, he knew Miochin must be there and called out to him, “Ha, Miochin, are you here?” Miochin came out to meet him. “Ha, Miochin, now I will destroy you.”

“Ha, Shakok, I will destroy you,” replied Miochin, advancing toward him, melting the snow and hail and turning the fierce wind into a summer breeze. The icicles dropped off and Shakok’s clothing was revealed to be made of dry, bleached rushes.

Shakok said, “I will not fight you now, but will meet you here in four days and fight you till one of us is beaten. The victor will win Co-chin-ne-na-ko.”

Shakok left in a rage, as the wind roared and shook the walls of White City. But the people were warm in their houses because Miochin was there. The next day he left for his own home in the south to make preparations to meet shakok in combat.

First he sent an eagle to his friend Yat-Moot, who lived in the west, asking him to come help him in his fight with Shakok. Second, he called all the birds, insects, and four-legged animals that live in summer lands to help him. The bat was his advance guard and shield, as his tough skin could best withstand the sleet and hail that Shakok would throw at him.

On the third day Yat-Moot kindled his fires, heating the thin, flat stones he was named after. Big black clouds of smoke rolled up from the south and covered the sky.

Shakok was in the north and called to him all the winter birds and four-legged animals of winter lands to come and help him. The magpie was his shield and advance guard.

On the fourth morning, the two enemies could be seen rapidly approaching the Acoma village. In the north, black storm clouds of winter with snow, sleet, and hail brought Shakok to the battle. In the south, Yat-Moot piled more wood on his fires and great puffs of steam and smoke arose and formed massive clouds. They were bringing Miochin, the Spirit of Summer, to the battlefront. All of his animals were blackened from the smoke. Forked blazes of lightning shot forth from the clouds.

At last the combatants reached White City. Flashes from the clouds singed the hair and feathers of Shakok’s animals and birds. Shakok and Miochin were now close together. Shakok threw snow, sleet, and hail that hissed through the air of a blinding storm. Yat-Moot’s fires and smoke melted Shakok’s weapons, and he was forced to fall back. Finally he called a truce. Miochin agreed, and the winds stopped, and snow and rain ceased falling.

They met at the White Wall of Acoma. Shakok said, “I am defeated, you Miochin are the winner. Co-chin-ne-na-ko is now yours forever.” Then the men each agreed to rule one-half of the year, Shakok for winter and Miochin for summer, and that neither would trouble the other thereafter. That is why we have a cold season for one-half of the year, and a warm season for the other.

The oldest tradition of the Acoma and Laguna peoples indicates they lived on an island off the California Coast. Their homes were destroyed by high waves, earthquakes, and red-hot stones from the sky. They escaped and landed on a swampy part of the coast. From there they migrated inland to the north. Wherever they made a longer stay, they built a traditional White City, made of whitewashed mud and straw adobe brick, surrounded by white-washed adobe walls. Their fifth White City was built in southern Colorado, near northern New Mexico. The people are finally obliged to leave

there on account of cold, drought, and famine.

Laguna, Spanish for “lake,” refers to a large pond near the pueblo. The word “pueblo” comes from the Spanish for “village.” It refers both to a certain style of Southwest Indian architecture, characterized by multistory, apartmentlike buildings made of adobe, and to the people themselves. The Pueblos along the Rio Grande are known as eastern Pueblos; Zuni, Hopi, and sometimes Acoma and Laguna are known as western Pueblos. The Lagunas call their pueblo Kawaika, “lake.”

Laguna and Acoma Pueblo Indians organized and instituted a general revolt against the Spanish in 1680. For years, the Spaniards had routinely tortured Indians for practicing traditional religion. They also forced the Indians to labor for them, sold Indians into slavery, and let their cattle overgraze Indian land, a situation that eventually led to drought, erosion, and famine. Pope of San Juan Pueblo and other Pueblo religious leaders planned the revolt, sending runners carrying cords of maguey fibers to mark the day of rebellion. On August 10, 1680, a virtually united stand on the part of the Pueblos drove the Spanish from the region. The Indians killed many Spaniards but refrained from mass slaughter, allowing them to leave Santa Fe for El Paso.

Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico

Isleta Pueblo, New Mexico

Jemez Pueblo, New Mexico

Kewa Pueblo, New Mexico

Nambé Pueblo, New Mexico

Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo, New Mexico

Picuris Pueblo, New Mexico

Pojoaque Pueblo, New Mexico

San Felipe Pueblo, New Mexico

San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico

Santa Ana Pueblo, New Mexico

Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico

Tesuque Pueblo, New Mexico

Zia Pueblo, New Mexico

North and South America had their own civilizations which flourished in pre-Columbian times. The western hemisphere’s population before the 15th century is estimated at about 100 million people. Unfortunately, most of these cultures have been lost or irreversibly altered by interaction with Western European culture. There is one case, however, that comes close – Taos Pueblo, the oldest continuously inhabited Puebloan settlement. Although it has some alterations, this site in New Mexico remains relatively unchanged since the days of the Ancestral Puebloans, still retaining native architectural styles and religious traditions. Taos Pueblo was first settled at some point in the 13th or 14th century, when the Ancestral Puebloans began to migrate into the area from the north in response to a drought that began about 1130 AD. This drought led to the abandonment of sites like Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon. The already marginal and arid climate of the region was rendered even more inhospitable by the drought and those locations were unable to sustain the relatively large population centers which had previously existed in the region.

Taos Pueblo: Evoking the Story of Ancestral Puebloans for 1000 Years

The Pueblo Indians, who built these communities, are thought to be the descendants of three primary cultures, including the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Ancient Puebloans, with their history tracing back to some 7,000 years. The term “pueblo” was first used by Spanish Explorers to describe the communities they found that consisted of apartment-like structures made of stone, adobe mud, and other local material. “Pueblo” also applied to the people who lived in these villages, which meant “stone masonry village dweller in Spanish.”

Cloud People – also known as the Shiwanna. In Pueblo Native American traditions, these are supernatural beings from the underworld who bring rainfall.

Shiwanna [Keresan mythology]

Pueblo mythology mentions the Shiwanna, spirits that travel on rainbows and bring rain to the world. They have a humanoid appearance, but they are powerful spirits Often associated with clouds, the Shiwanna are the spirits of the dead, and spirits of deceased humans were traditionally represented with clouds. They supposedly live in the mountains, but can also be found living underneath lakes and ponds or near human settlements close to the sea. They seem to be relatively unknown, as I could find very little information about them. If I am not mistaken – I might be – there are only 4 Shiwanna in existence, at least in Keresan religion. But the details seem to differ between tribes and stories. Regardless, these beings live in Wenima, a mythical blessed location that can be compared to the Christian idea of Heaven.

Anasazi Heritage Center

Black Mesa, Arizona

Butler Wash Overlook, Utah

Casa Grande National Monument, Arizona

Chimney Rock Archeological Site, Colorado

Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, Colorado

El Morro National Monument, New Mexico

Escalante Ruin, Colorado

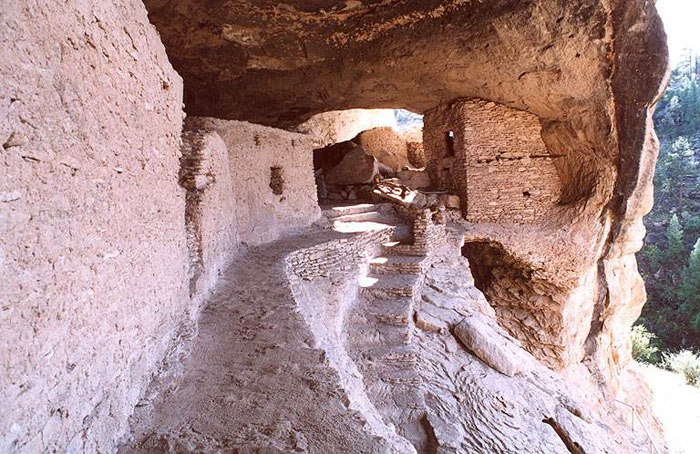

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, New Mexico

Homolovi Ruins State Park, Arizona

Kinishba Ruins, Arizona

Lowry Ruins, Colorado

Montezuma Castle National Monument, Arizona

Mule Canyon Ruins, Utah

Navajo National Monument, Arizona

Pojoaque Pueblo, New Mexico

Pueblo del Arroyo at Chaco Canyon

Pueblo Grand Ruin, Arizona

Pueblo Grande de Nevada

San Estévan del Rey Mission at Acoma Pueblo

Salmon Ruins, New Mexico

Taos Pueblo, New Mexico

Tonto National Monument, Arizona

Tuzigoot National Monument, Arizona

Walnut Canyon National Monument, Arizona

Wupatki National Monument, Arizona

Ute Mountain Tribal Park, Colorado

The Ancestral Puebloans were an ancient Native American culture that spanned the present-day Four Corners region of the United States, comprising southeastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, and southwestern Colorado. The Ancestral Puebloans are believed to have developed, at least in part, from the Oshara Tradition, who developed from the Picosa culture. They lived in a range of structures that included small family pit houses, larger structures to house clans, grand pueblos, and cliff-sited dwellings for defense. The Ancestral Puebloans possessed a complex network that stretched across the Colorado Plateau linking hundreds of communities and population centers. They held a distinct knowledge of celestial sciences that found form in their architecture. The kiva, a congregational space that was used chiefly for ceremonial purposes, was an integral part of this ancient people’s community structure.

Naiyenesgani Rescues the Taos Indians

Naiyenesgani went among the Pueblo Indians. While there he stole and concealed their corn. When they came to him, they said, “Apache, go outside.” Naiyenesgani made a motion over the corn with his hand, and it became snakes. Then they were friendly to him. He put his hand over the place again and there were piles of corn as before. Again, they said, “Apache go outside.” He made passes before the piles of corn and they turned into snakes which moved about. Again, they became friendly with him. He moved his hand over the place and the corn lay in rows again. “Go outside Apache,” they said again. He moved his hand over the corn. The rows changed into snakes having wings. “Shut the door,” he said. They commenced throwing the corn away. They shut the door. They came to Naiyenesgani who passed his hands over the place again and the corn lay in rows. “You certainly are a medicineman,” they said. “Over here is a sinking place where our people have been taken into the ground away from us.”

Pueblo peoples have lived in the American Southwest for thousands of years. Their ancient ruins, particularly Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings, are among the most spectacular ancient ruins in North America. By the end of the severe, prolonged droughts in the late fourteenth century they had relocated to the vicinity of their modern communities primarily located within the watershed of the upper Rio Grande River Valley in New Mexico and the watershed of the Little Colorado River in Arizona. The pueblo tribes represent several distantly related language families and dialects, and they have continued to maintain close contact with each other since the arrival of Europeans in the region in the sixteenth century. Today the 19 pueblos of New Mexico cooperate in a loose confederation called the All Indian Pueblo Council. Each pueblo is autonomous and has its own tribal government. The Pueblos have been able to retain a tribal land base, retain a strong sense of community, and maintain their languages and cultures. The name Pueblo is the same as the Spanish word for village and denotes both the people and their communal homes. No one knows precisely when Pueblo peoples first arrived in the Southwest, but they are believed to be descended from Archaic desert culture peoples.

HISTORY OF PUEBLO NATIVE AMERICANS

Pueblo Native Americans are one of the oldest cultures in the United States, originating approximately 7,000 years ago. Historians believe the Pueblo tribe descended from three cultures, “including the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Ancient Puebloans (Anasazi).” Representative of the Southwest American Indian culture, the Pueblo tribe settled in the Mesa Verde region at the Four Corners of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona. Due to limited natural resources or intertribal conflict, in the 1300s, the Pueblo people migrated south and primarily settled in northeastern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico. Following Christopher Columbus’ voyage to the New World, Spain embarked on claiming various North American territories. In the 15th century, Spanish colonization’s detrimental effects befell the peaceful Pueblo tribes — resulting in censorship of Pueblo culture and religious practices. By the 1670s, Pueblo revolts forced the Spanish to flee, and the Pueblo people were able to return to their generation-long cultural practices. Years later, once the Spanish returned and re-colonized, many Native American tribes were forced to adapt to the dominant culture as a means of survival, and this history of trauma has impacted the Pueblo people to this day.

Ancestral Pueblo prehistory is typically divided into six developmental periods. The periods and their approximate dates are Late Basketmaker II (AD 100–500), Basketmaker III (500–750), Pueblo I (750–950), Pueblo II (950–1150), Pueblo III (1150–1300), and Pueblo IV (1300–1600). When the first cultural time lines of the American Southwest were created in the early 20th century, scientists included a Basketmaker I stage. They created this hypothetical period in anticipation of finding evidence for the earliest stages of the transition from hunting and gathering economies to fully agricultural societies. By the late 20th century archaeologists had concluded that Basketmaker II peoples had actually filled that role. Rather than renaming Basketmaker II and III to reflect this understanding of the evidence, Basketmaker I was generally eliminated from regional time lines, although some scientific discussions about its role in regional chronologies continued in the early 21st century.