Lithuanian mythology (Lithuanian: Lietuvių mitologija) is the mythology of Lithuanian polytheism, the religion of pre-Christian Lithuanians. Like other Indo-Europeans, ancient Lithuanians maintained a polytheistic mythology and religious structure. In pre-Christian Lithuania, mythology was a part of polytheistic religion; after Christianisation mythology survived mostly in folklore, customs and festive rituals. Lithuanian mythology is very close to the mythology of other Baltic nations – Prussians, Latvians, and is considered a part of Baltic mythology.

The only Devils’ Museum in the world, the Hill of Witches, Amber museum boasting Baltic Sea treasures, the monster of the Vilnius dungeons: these and other places, alluring children and adults alike, prove that fairy tales and legends are alive and well in Lithuania. Most of these legends stem from authentic Lithuanian folklore tales and Baltic mythology. Visiting these mysterious spots will make your trip an unforgettable experience and allow you to better understand the country’s culture. The Devils’ Museum, listed as one of the most unique museums in existence, contains around three thousand exhibits from all over the world – works of fine art, applied art, souvenirs and masks. The museum provides a great opportunity to have a closer look at how mysterious mythological creatures are depicted across more than 70 countries, including Lithuania. The collection was started by the famous Lithuanian painter Antanas Žmuidzinavičius, and the museum continues growing with the help of its visitors. – You can also donate a devil artefact to the museum.

Lithuanian Museum of Ethnocosmology

“Žiburinis”, drawn by me. Žiburinis – an evil spirit in lithuanian mythology, usually taking shape as a flourescent skeleton or a skeleton with a candle or an open flame in its chest.

Gods and goddesses of the pagan pantheon are not forgotten in the street names either, including Žemyna, Gabija, Medeina and, of course, Perkūnas. Among the mythological figures the fisherman Kastytis and sea princess Jūratė (two doomed lovers) are the most popular. A howling Iron wolf, the subject of a legendary grand duke Gediminas’s dream interpreted by pagan priest Lizdeika as an instruction to establish Vilnius city, is an another well-known myth “character”, used as a symbol of Vilnius and Lithuania on many occasions. Lithuanian mythology and folklore are closely intertwined. While Lithuanians have been the last European pagan great power to Christianise the pagans never had religious books and thus much of the old religion has survived in the folklore alone. What were once deities may have been relegated to mythical creatures or natural forces in later folktales, however.

The Top 10 Lithuanian historical figures of all time

With more than 100 different versions recorded around Lithuania, this folktale is one of the best-known in the country. It’s also my absolute favourite – but I’ll try to keep this retelling relatively short. In the distant past, a young maiden was bathing in the river with her two sisters. When she gets out and puts on her clothes, she finds a grass snake in the sleeve of her blouse. She tries to shake it off, but it speaks to her in a human voice, insisting she marry it in exchange for leaving. Bit of an unfair trade, but eventually the distraught young woman accepts. After three days, thousands of snakes slither to her home to claim her as their queen and wife to their master. But Eglė’s horrified family trick them three times, into taking a goose, a sheep, and a cow as their master’s bride. Each time they return to the family when they notice the ruse, until finally they threaten a year of famine if she doesn’t go with them. When they finally see Eglė again, her family doesn’t want to let her go. So, in an attempt to learn how to summon her husband, they beat the couple’s sons. They won’t betray him though, until the frightened young daughter gives in and tells them the chant. Eglės twelve brothers call on the Grass Snake Prince, and kill him with scythes when he emerges from the water. Eglė only discovers the betrayal days later, when she speaks the chant, and finds nothing but bloody foam. Inconsolable over the death of her beloved, the serpent queen whispers an enchantment, and turns her daughter, who betrayed them through her fear, into a quaking aspen. She then turns her three sons into mighty trees, an oak, an ash, and a birch tree. In a final act of magic, Eglė transforms herself into a spruce.

KING AND QUEEN OF THE SERPENTS

So Eglė is taken to their king, who lives at the bottom of the sea. But instead of seeing another snake, she meets a handsome young man – Žilvinas, the shapeshifting Grass Snake Prince. Pleasantly surprised, and more than a little relieved, Eglė finds that she enjoys the man’s company, despite circumstances. He shows her the beautiful palace she is to spend eternity with him in, and they spend three weeks feasting and being merry, the newlywed King and Queen of the serpents. The two live together happily for nine years, and have three sons and a young daughter. Eglė forgets about her own life, until one day her son asks about her parents. Feeling suddenly homesick, Eglė decides to return home for a visit – but her husband forbids her from leaving. When she insists, he sets her three impossible tasks. Eglė must spin a never-ending thread of silk. Wear down a pair of iron shoes. And bake a pie with no utensils. With help from a sorceress, Eglė completes these unusual tasks. Žilvinas honors the agreement, and lets her go, taking their children to see her family. First though, he instructs them all on how to call him from the sea, and swears them to secrecy.

JŪRATĖ AND KASTYTIS

A far shorter, and similarly popular Lithuanian folk tale, Jūratė and Kastytis follows two star-crossed lovers. Interestingly, the tale reportedly comes from the 19th century and isn’t ancient at all. But it’s certainly popular, and lovely (if sad) enough to be well worth the telling. In a time when gods still roam the earth, the sea goddess Jūratė lives in an amber palace beneath the sea. There, she rules over the creatures of the Baltic ocean, their protectress. A young fisherman, Kastytis, begins to disturb the peace of her domain, catching too many fish on the coast. Jūratė decides to punish him, but when she sees the young mortal man, she falls instantly in love. The two become lovers, and live for a time in Jūratė’s amber castle. But one day, the thunder god Perkūnas discovers their relationship, and grows furious at the goddess for stooping to the level of their mortal creations. And so he strikes her amber castle, shattering it into a million pieces and killing Kastytis. Worse, he chains the goddess to the ruins, leaving her there to mourn her loss for eternity. In some versions of the story, it is Jūratė’s tears that form the amber pieces that wash ashore in Lithuania. In others, Baltic amber is the remaining pieces of her ruined castle.

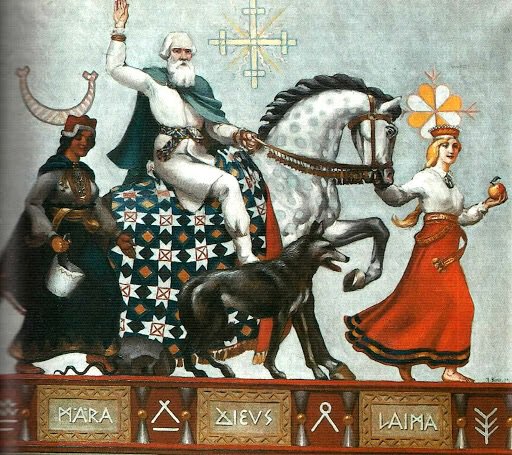

Most information regarding Latvian mythology stems from folkore and folk songs as well as Livonian Chronicles. Latvian mythology exhibits the least amount of male deities and has preserved the cult of Mother Goddess or The Mother of Gods, widely attributed to the matriarchal cult of pre-Indo-Europeans. During the romanticism period of the 19th century, there have been fabricated figures by the authors who were trying to reconstruct a Latvian pantheon using information from neighboring regions. However, this doesn’t diminish the deities that did survive and are provided below.

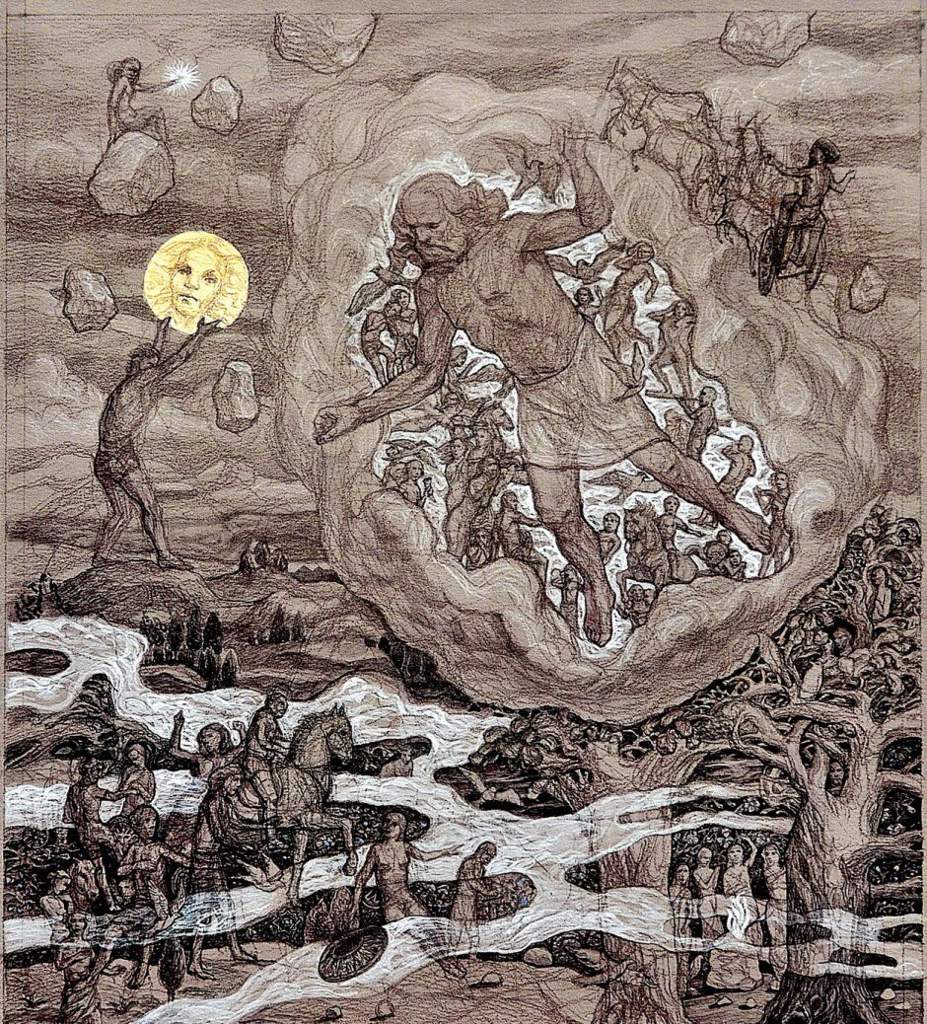

Lithuanian Mythology. The gates of the Earth

Māte – The mother goddess

Bangu māte – mother of waves

Ceļa māte – mother of roads

Dārza māte – mother of gardens

Dēkla māte/ Kārta māte – sisters of Laima

Jūras māte – mother of seas

Kapu māte – mother of graves

Krūmu māte – mother of bushes

Lapu māte – mother of leaves

Lauka māte or Lauku māte – mother of fields

Lazdu māte – mother of hazel trees

Lietus māte – mother of rain

Linu māte – mother of flax

Lopu māte – mother of livestock

Miglas māte – mother of mist

Smilšu māte – mother of sand

Sniega māte – mother of snow

Tirgus māte – mother of market places

Ūdens māte – mother of water

Upes māte – mother of rivers

Vēja māte – mother of wind

Veļu māte – mother of souls

Zemes māte – mother of earth

Ziedu māte – mother of flowers

Sources of Lithuanian gods and goddesses can be found in the Chronicle of John Malalas, a Byzantine chronicler, the Hypatian Codex, folklore and folk songs. They show a distinction between deities worshiped by the nobles and agriculturists. The king of Lithuania, Mindaugas (1253-1263) was said to worship Diviriksas (presumably an epithet of Perkūnas), Teliavelis, Nunadievis (presumably an epithet of Dievas) and Medeina – mostly male gods related to war, strength and the hunt. Common folk worshiped Žemyna, Saulė, Ganiklis, Gabija – mostly female gods related to the earth and the household. Lithuanian mythology also had not escaped the romanticization of the pantheon and beliefs. Polish-Lithuanian historian Teodoras Narbutas is infamous for his unverified lists of deities, not met in any other documents or folklore.

Dievas

Perkūnas

Velinas/Velnias

Gabija

Žemyna

Laima

Medeina/Žvorūna

Aušliavis

Ganiklis

Šeimos dievas

Kelių dievas

Bubilas

Austėja

Šventpaukštinis

Pušaitis

Aušrinė

Vėjopatis

Upinis

Ežerinis

Žiemininkas

Saulė

Ragana

Teliavelis

Milda

Junda

Rasa

Jūratė